Planning a wedding is no easy task. One must pick a date, hall, caterer, band, florist, and on and on it goes. For those living in North America (and I presume most everywhere else except Israel), having a Sunday wedding is most desirable. With no need to worry about people's work schedules, one can start and end a bit early. Those coming from out of town can fly in the morning making an afternoon wedding a viable option.

None of this held true in Talmudic times, and not only because Sunday was a workday like any other. "A betulah, virgin marries on the the fourth day (Wednesday evening), and a widow on the fifth [day]". As to why this is so, the Mishnah explains, because "twice a week the beit dinsits in the cities on the second day (Monday), and on the fifth (Thursday), so that if he had a claim of virginity, he would get up and come to the court" (Ketubot 2a). When a young, Torah observant couple marries, it is a reasonable assumption that they are virgins--and if not, one would expect that to be communicated beforehand. It is only due to this assumption that the husband agrees to obligate himself to the standard 200 zuz of the ketuba[1]. The ketuba for non-virgins was set at half the value of that of a virgin, or 100 zuz. Discovering that his wife is not a betulah might be a great shock and disappointment to the husband--and if so, he would be under no obligation to honour the full amount of the ketuba.

However, our Sages were concerned with a more serious problem, that of adultery. As we discussed in our introduction to Ketubot, it was common to have eirusin, the first step of the wedding (today done by the giving of the ring) up to year before the nissuin, the taking of the wife into the husband's home. Thus, the timing and method of her loss of virginity becomes crucial. If it was due to her having an affair with another man in the time period between eirusin and nissuin, then that is adultery, plain and simple. As such, the newlywed couple would be forced to divorce, in keeping the with law of "assura lebaal veassura leboel" (Sotah 25a), that she is prohibited both to her husband and her lover. Our Sages expected a man who, quite to his surprise and chagrin, discovers on his wedding night that his wife is not a betulah to be angry and to run to the court the next morning to possibly end the marriage. Our Sages feared that if the wedding took place on a Monday night, during the ensuing two days he might "be appeased and cool down" (Rashi) and not even bother coming to (divorce) court.

If the wife was (even if in violation of Jewish law) sexually active before meeting her husband or she lost her virginity in some other fashion, we would welcome the couple moving on and building a home together. But if not, then the marriage must end. To help ensure that the husband would come to court, which would then properly investigate the matter, they instructed that the wedding should take place on Wednesday evening [2], minimizing any potential excuses not to go to beit din.

Of course, based on this, one could get married on a Sunday night--the beit din sat on both Thursdays and Mondays. However, there was an additional, most pragmatic reason our Sages instructed us to marry on Wednesday as opposed to Sunday evening. "The Sages watched over the interests of the daughters of Israel so that [the bridegroom] should prepare for the meal three days, the first day of Shabbat, the second of Shabbat, and the third day of Shabbat, and on the fourth day he marries her" (Ketubot 2a). Catering for a wedding without modern appliances, not to mention refrigeration, was no easy task. It took at least three long days of work; having Shabbat interrupting preparations was not a good idea. Let the work begin on Sunday, and the celebrations on Wednesday night[3]. Mazal-tov!

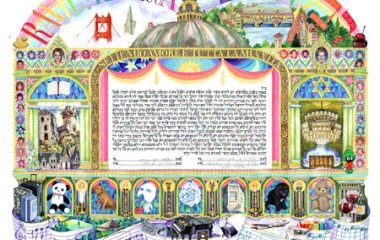

[1] Translating the value of the ketuba into Canadian dollars is not an easy task. Our ketubot actually use 200 zekukim, a medieval German coin estimated in value anywhere between 8 and 45 kilos of silver. For the majority of people who do not actually use the values of the ketuba, such matters little. For those who do--something more common amongst Sefardim and Israelis--they will specify an actual amount based on the currencies in use today.

[2] I imagine that for many who might be learning this for the first time, this comes as a rather jolting opening to the tractate that discusses the laws of marriage. One must realize that, with the exception of the Pirkei Avot, the Mishnah is a legal code, not a moral one. It deals not with how life should be, but how it often is. The opening Mishnah of the Talmud discusses whether the children of Rabban Gamliel could say the Shema after returning home late from a party, missing the regular time of shema. Masechet Shabbat opens with a poor person being left out on the street trying to get some food from a wealthy homeowner without violating the laws of carrying. Seder Nezikin opens by describing the damages I must pay when I or my possessions cause damage; Seder Kodshim open with someone bringing a sacrifice with either no intent, or the wrong intent; and on and on it goes. Law is specifically needed for those who, purposely or not, may violate it.

[3] In Talmudic times, it was the bridegroom who paid for the meal at the wedding.