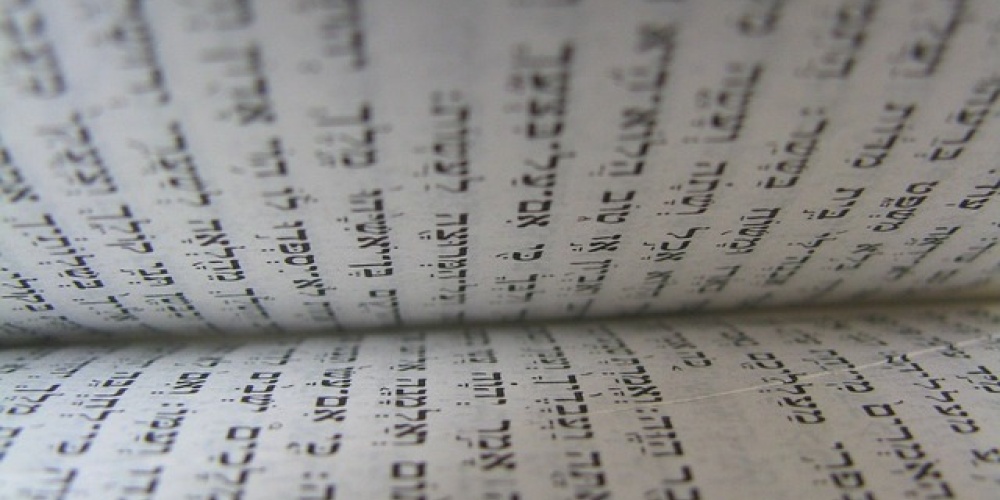

Fundamental to Jewish theology is the belief that both the Written Law and the Oral Law were given by G-d at Sinai. While the finite Written Law, i.e., the Torah, contains the words of the Divine Lawgiver, the ever-expanding and infinite Oral Law reflects man’s interpretation of the Divine text.

The perspectives of the Divine and humans are very different; in fact, the human mind cannot fully, if at all, fathom the Divine. While we focus on G-d’s attributes of mercy over the Yamim Noraim, G-d is also the vengeful and “jealous G-d” punishing those who defy His authority. It is this aspect of G-d that He revealed to us at Sinai, and it is part and parcel of the aseret hadibrot.

The merciful, compassionate, patient, forgiving G-d is one we are only introduced to later, with His forgiveness for B’nei Yisrael’s sin of the Golden Calf. One might even view Sefer Breisheet as G-d teaching man the price of disobedience: banishing Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden; banishing the nomad Cain from human society; the flood; the Tower of Bavel; Sedom and Amorah; the rejection of Lot, Yishmael and Eisav from participating in a covenantal relationship with G-d.

While we might call this punishment, it is actually an application of Divine justice. As Rashi notes on the opening verse of the Torah, G-d “intended” to create a world based on strict justice. However, such a world can exist only in pre-human times. Once G-d creates man, because there is no man who does not sin, He must introduce mercy to the world. Without such, humanity would cease to exist.

The Torah is full of so much mercy, kindness and compassion, much of which was absolutely revolutionary[1]. We are to love our neighbour, the stranger and the convert; we must show extra compassion to the widow and orphan and help the poor in so many ways, even letting them wander in our fields looking for food. There was to be one justice system for all—whether citizen, resident alien or foreigner. The Torah is the most sublime of moral codes.

Yet we dare not ignore the harsh justice the Torah prescribes. “They shall surely be put to death” is a refrain we hear over and over again. Sinners are stoned and burned, the lucky ones are given lashes only, wayward children who disobey their parents (are there any children who can be excluded?) are to be stoned by “all the people of his city”, entire (Jewish) cities whose inhabitants “worship other gods” are to be destroyed. Even if G-d may have mercy on sinners, such may only be temporary as “He visits the sins of the fathers upon their children”.

Yet the Oral Law—written by humans, but reflective of the Divine will—has seemingly done away with much of the above. The death penalty was almost never implemented, and Rabbi Akiva boasted that had he been on the court, it would have never been meted out. When the death penalty was decreed, it was not carried out literally by stoning, and surely not by burning anyone at the stake. And sins of the parents were not visited on their children unless they, too, were deserving of punishment. Regarding the wayward son and destroyed cities, our Sages went so far as to declare that such cases “never happened and never will happen” (Sanhedrin 71a).

While all societies have laws on the books that were once applicable, but no longer are, the Torah has laws on the books that were never applicable and never will be. While it is understandable that a human law book may not be fully updated, surely there is no place for outdated (or never dated at all) laws in a Divine work meant for all eternity. Thus, our Sages were perplexed and asked, “So why was it written? [So that we should] study and get reward.”

Yet this answer just compounds the question. What is the point of studying something that has zero applicability? Is there not enough to study already? And what right do we have to study the (not even) theoretical when there is so much practical law that needs more of our attention? And since when is getting a reward a reason for study?

The Torah, however, is much more than a law book. It is actually a description of G-d—His autobiography, if you like. And we must study all aspects of the Divine, even (especially?) those parts that are in heaven only, with no application on earth. The more we learn about G-d, the more we learn about ourselves, created in the image of G-d.

So what might we learn from the rebellious child? It could be argued that the primary lesson is to think long term. Our Sages note that this rebellious child, while he may not be a paragon of kibbud av v’eim, and may eat and drink too much, has done nothing worthy of the death penalty. Yet he is to be killed al shem sofo, because of what is likely to do – “so that he may die meritorious and not guilty” (Sanhedrin 71b). One may start with petty crime, drug use, cheating and the like, but if it continues and is not nipped in the bud, we may end up with much worse.

Of course, Jewish law does not allow one to be killed because of what one might do[2] and this may have been what led the Sages to claim such a law could never have been meant to apply in real life. Only G-d can decide whether to punish now for what they may do in the future. But while we can’t punish, we can learn—always a more effective strategy. And more important than a warning to any child, the laws of ben sorer u’moreh are a warning to parents on the importance of early intervention[3].

The laws of a destroyed city, ir nidachat, teach us that an entire society can lose all sense of morality, a lesson that needs no emphasis in a post-Holocaust generation.

There is a third Torah law the Gemara claims never has and never will be implemented: that of a leprous house, which must be destroyed. It is a mini-ir-nidachat, teaching that a home can be so empty of moral value that it needs to be rebuilt from the bottom up.

[1] It is because so much of the Torah’s vision of society has been accepted in the Western world that we often fail to realize how revolutionary are the ethical and moral teachings of the Torah. It is a pity that so many equate Torah with ritual, and not the powerful moral messages it brought to the world – even as the world resists some other of the Torah's messages from which it would greatly benefit.

[2] This lesson is derived from Yishmael, who may be the ancestor of many killers, but who did little wrong himself and would not be punished. In fact, our Sages claim he did teshuva at the end of his life. A related idea is seen in Yishayahu’s rebuke of Chizkiyahu, who did not want to father a child, as he saw in a vision such a child would be the worst of all the kings of the Jewish people. “What have you to do with the secrets of the All-Merciful?” Yishayahu asked him. Chizikaya listened, and his son Menashe was the worst of all the kings of the Jewish people (see Brachot 10a).

[3] With Sukkot in a couple of days, this is a most timely message, as it is the holiday of Sukkot that emphasizes the mitzvah of chinuch, preparing our children for adulthood. The evidence for such is beyond the scope of this devar Torah, but for now I will just point out that the laws of chinuch are found in masechet Sukkah.