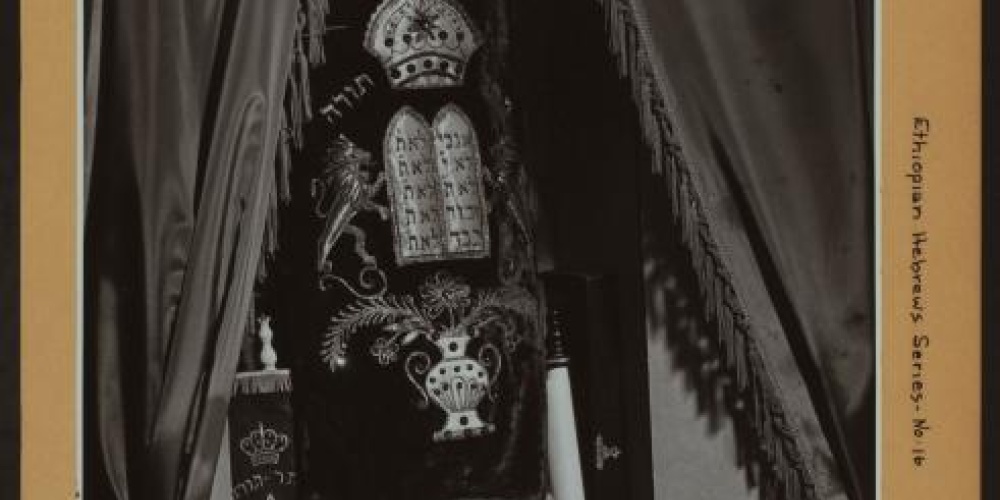

“Rava said: How foolish are the rest of the people who stand before a sefer Torah, but do not stand before a great person!” (Makkot 22b). Walk into any shul when the sefer Torah is being taken out, or even when the ark is opened[1] and the Torah scrolls remain inside, and you will see everyone standing. How can one not stand for a sefer Torah?

Rava continues to explain why: “As in the sefer Torah, it says one gets 40 [lashes] and the rabbis came and removed one”, such that we give "only" 39 lashes. This is a simple but concrete example of how, without rabbinic input, we would apply the Torah incorrectly.

But Rava is teaching much more than that. Almost every verse in the Torah requires rabbinic input to explain its meaning, and Rava could have chosen myriad examples to demonstrate how rabbis taught us that we dare not follow a literal interpretation of the Torah. But he chose this one, which seems a blatant contradiction of the biblical text that clearly states one who receives lashes is to be whipped 40 times, until the rabbis “came” and “made it one less.”

The mark of a great rabbi – and note how Rava refers to them not as great rabbis, but as great people[3]—is that he lowers the amount of human suffering, even if only by some two or three percent. While one may not change or ignore a text, one can and must interpret it (and our Sages were given wide interpretive powers). And more often than not – perhaps always – a text can be interpreted in more than one way.

Great people will interpret the text in a manner that reduces suffering for people. It is why our Sages rule that, “the power of leniencies is greater” (Beitza 2b). As Rashi explains, “anyone can be stringent”, but it takes a great person to be lenient, one who “relies on what he hears and is unafraid to permit”. It is why, generally speaking, the greatest of our poskim—people like Rav Moshe Feinstein or Rav Ovadiah Yosef—were known as meikilim, those who sought leniency. It is why Rav Yitzchak Elchanan Spector, the greatest posek of the last part of the 19th century, devoted his life to freeing agunot, coming up with new and original halachic arguments that no one had used before him[4]. And it is why the greatest Talmudic genius of the 19th century, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, said that the role of the rabbi is to help the needy, to care for the widow, the orphan and the poor.

Of course, not every interpretation is valid, nor do those who are not masters of the text have the right to interpret it. At times, no matter what interpretation we may want to give, the verse cannot be made to mean something it does not. In our Mishna – and Rava is speaking of the Mishnaic interpreters of the text[5] – our Sages understood the verse, “40 [times] you shall lash him, you shall not add” (Devarim 25:3), to refer to “a number that is next to 40” (Makkot 22a). When one considers the Biblical tendency to use round numbers, this interpretation is most reasonable.

While the discussion of the number of lashes one gets is of little significance today, Rava’s teaching is all too relevant. Do we not often emphasize that which is of much lesser importance, often at the expense of the truly important? How often do we adopt chumrot, stringencies, when we have so much work to do in basic mitzva observance? How foolish are those who argue about whether to say tachanun but barely stop talking during chazarat hashatz? Who insist on rigorous stringencies in kashrut but rely on the most lenient views regarding their business dealings (or none at all)? Who spare no expense in purchasing ritual objects but give as little to tzedakah as possible? Or who are so respectful of the dead but when it comes to the living, leave much to be desired?

[1] Contrary to popular belief, while it may be laudable, there is no requirement to stand while the ark is open. Only when the Torah is taken out and not yet placed on the teiva must one stand.

[2] One can debate whether it is worse to be declared a rasha, an evil person, or a fool.

[3] While the halacha demands that we stand for great people who are not Torah scholars, too—i.e., a communal leader—it is clear from the context that Rava is specifically referring to Torah scholars.

[4] I recall Rabbi Moshe Tendler saying that by far, the most important teshuva his father-in-law, Rav Moshe Feinstein, wrote, was the one permitting Holocaust survivors to remarry, despite lacking evidence that their spouses had died. With the modern methods of communication available—and this teshuva was written in the 1940s—if one did not hear from one's spouse, Rav Moshe ruled that one could assume they had been killed. It was this teshuva—one that all knew was not 100% foolproof—that allowed survivors to begin to rebuild their lives.

[5] In fact, it could very well be that the fundamental difference between the tanaim and the amoraim, the sages of the Mishna and those of the Gemara, is that the former had the right to offer new interpretations of Biblical text, whereas the latter could only do so regarding the words of their predecessors but had no right to “invent” new interpretations of biblical text.