One of the major debates in Jewish law is whether mitzvoth require kavanah, intent to fulfill the mitzvah (see for example Brachot13a). As a general rule, those mitzvoth which are dependent on actions--for example, shaking a lulav or eating matzah--are mitzvoth for which kavanah, while ideally present, is not required; after all, I did what I had to do. Those mitzvoth for which it is our inner thoughts or feelings that matter most--for example, accepting the yoke of heaven through recital of the first verse of the shema--kavanah is crucial[1].

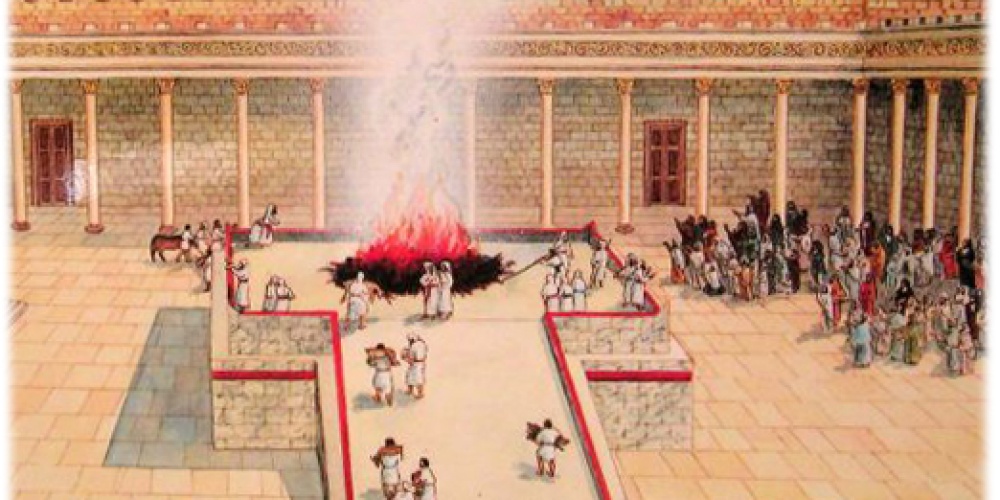

This is especially so regarding korbanot, where even the slightest inappropriate thought may render the korban invalid. Korbanot, more than any other area of Judaism, depend on our inner feelings. It is for these reasons that our prophets, time and time again, ridicule and castigate those who think that the act of bringing sacrifices has independent value. Minus intent to mend one's ways, a sacrifice becomes a debasement of religion(see for example, Yishayahu, 1).

The importance of absolute fidelity of thought and action is expressed in the notion of pigul, the prohibition to sacrifice an animal that one intends to eat beyond the allotted time. Similarly, if one intends to offer the sacrifice in a different place--even if one does not actually do so--the korbanot are invalidated. In the former case, eating such a sacrifice carries the penalty of karet, excision, no different than eating on Yom Kippur or "marrying" one's aunt.

The mitzvah of ketoret requires that one take a handful of spices and burn it on coals taken from the altar. The Gemara (Yoma 48a) rules that if one scoops the spices with the intent of burning them the next day, the ketoret would be invalid. The Gemara then raises the question of whether pigul would apply regarding the removal of the coals on which the ketoret is to be burned. The Gemara explains that the resolution to this question is dependent on whether machserei mitzvah k'mitzvah dami--is the preparatory stage of a mitzvah the same as a mitzvah itself?

The Gemara, unsure as to the status of hechsher mitzvah, leaves the question unresolved; teiku, it shall stand[2].

The Gemara's response reflects much more than uncertainty; it is the only possible answer to the question. Whether the preparatory stages of a mitzvah are a mitzvah is dependent on what happens next. If one builds a sukkah but does not sit in it, little has been accomplished. If one carries through and completes the mitzvah, then all the steps leading up to the mitzvah are part and parcel of the mitzvah. A hechsher mitzvah stands in suspension, "waiting" for the next steps.

The actions we take today impact on the present, the future, and the past. They demonstrate not only what we hope to accomplish, but whether our prior efforts have been put to good use or were a waste of time. Our lives are full of teiku, of things that are standing in abeyance waiting for what will happen next. It is up to us to determine whether our past efforts have been well spent or wasted. A lot of good work is lost for want of a little more. It is our task to put in that extra effort so that teiku, that which stands, can move forward[3].

[1] The details of when kavanah is or is not required, and the definition of kavanah itself are subject to much debate and nuance and is beyond the scope of this thought (see Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 60:4). A fascinating question is whether kavanah is crucial in the realm of mitzvoth between man and man.

[2] While many were taught at a young age that teiku is an acronym for Tishbi yetaretz kushiot veubayot, that Eliyahu Hanavi will answer all unresolved questions in the Messianic Age, such was said as a means to inculcate a yearning for and belief in the coming of the mashiach. It reflects a historical truth, but not a legal one. In fact, Jewish law rules that a prophet may not answer halachic questions, that being the domain of more earthly rabbis.

[3] Perhaps this reflects another idea of teiku and Eliyahu. If we do not follow through on our efforts, we shouldn't expect others to do so; and it will wait a long time--until the Messianic Age--to be fulfilled. In such a case, teiku is not belief in the future, but is a rebuke to us for waiting for the Messiah to solve our problems.