"One should be as careful with a light mitzvah as with a heavy mitzvah" (Pirkei Avot 2:1). Not every mitzvah is created equal. While all emanate from G-d at Sinai, some mitzvoth are more important (heavy) than others (light). Shabbat is, for example, more important than kashrut, and Yom Kippur is more important than Tisha B'av[1].

One of the primary ways we can tell which mitzvoth are more important is by seeing what punishment the Torah proscribes for violating a particular mitzvah. By prescribing (human) punishments for violations of negative commands only, the Torah signals that acts of commission are (generally) more serious than acts of omission. Those sins for which one is (theoretically) liable for the death penalty are of greater importance than those which carry "only" the punishment of lashes.

Yet, "My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways My ways, said the Lord" (Yeshayahu 55:8). While from a divine perspective, the death penalty is the most severe punishment, such is not necessarily the perspective of man. As the recent decision of the Supreme Court of Canada allowing doctor-assisted suicide demonstrates, pain can be, in the eyes of people, much worse than death.

As we mentioned in our last post, one can only be given one punishment for one action, even if two would be warranted. What, then, should be the punishment if the same action requires a monetary penalty and lashes? Such would be the case, for example, of edim zomemim, plotting witnesses, where one falsely testifies that Reuven owes Simon $100 and is shown to have been elsewhere at the time of the supposed loan. One is theoretically liable to both pay $100--"and you shall do to them what they plotted to do to their brother" (Devarim 19:19)--and receive lashes for lying. While in this particular case, the Talmud says that the witnesses pay and do not receive lashes, the Gemara notes that one may not extrapolate from here to other cases where there is both a monetary fine and lashes to be had. That is due to the fact that, for lashes to be administered, a warning must have been issued immediately prior to one's action, something that is not practical in this situation.

The Gemara instead turns to analyzing the case of abortion--one that may potentially involve assault or even murder. "And if men strive together, and hurt a woman with child, so that her fruit depart, and yet no harm follow, he shall be surely fined, according as the woman's husband shall lay upon him; and he shall pay as the judges determine. But if any harm follow, then you shall give life for life" (Shemot 21:22-23).

In order to even have the possibility of giving a death penalty, the perpetrator would need to have been warned of a possible death penalty. Such would be the result if he kills his fellow man. Yet if, in attempting to hit his fellow man, he "mistakenly" hits the pregnant woman (wife?) and aborts the fetus, one would presumably get lashes for assault. (The killing of the potential life of a fetus, as serious as it may be, does not reach the level of murder.) As for the fact that no warning was given for lashes, such is not an issue, as "one who is warned for something severe (death) is considered warned for something light [lashes]" (Ketubot 33a).

Yet the Torah stipulates that if the victim is "only" injured, the perpetrator is to be fined, apparently proving that when one is liable for monetary payment and lashes, it is the monetary payment that would be imposed.

To this, the Gemara gives two responses. Perhaps monetary payment (for which no prior warning is needed) is given because one needs a specific warning for lashes, and a warning for death would not suffice. The perpetrator may have ignored a warning about death, thinking he would never kill the other, but had he known about lashes, he might not have hit him at all.

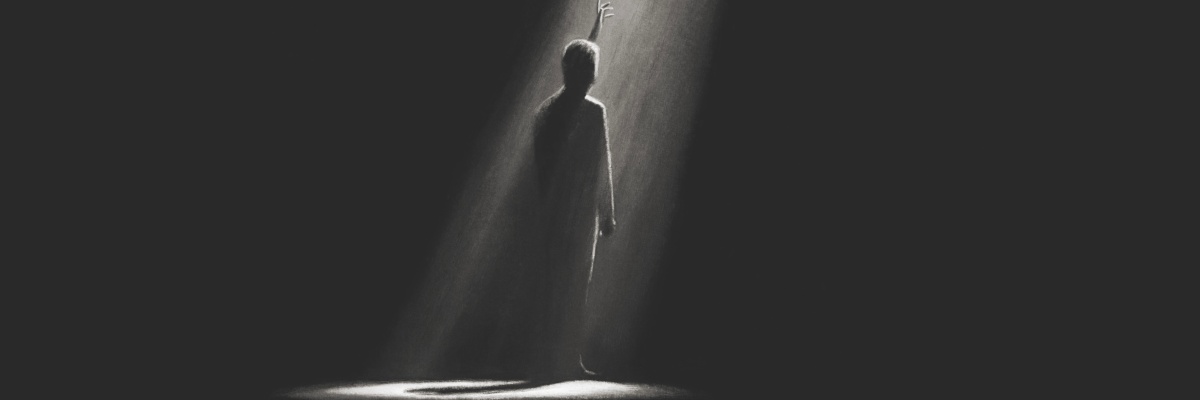

Even if one were to accept the premise that being "warned for something severe is considered warned for something light", "who says death is more severe? Perhaps lashes are more severe, for Rav said: 'If they had lashed Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah, they would have worshipped the image'" (Ketubot 33a-b).

There are causes that one may be willing to die for, but for which they are unable to withstand ongoing torture for. It is true that the death penalty is given for only the gravest of sins, but many would prefer death to pain. Not all are capable of reaching the levels of Rabbi Chananiah ben Tradyon, who would not hasten his death even as he was being burned alive (Avodah Zara 18a). And while it is well known that one is mandated to give up his life rather than transgress one of the three cardinal sins of idolatry, adultery, and murder, one who does transgress is not held liable for the murder or adultery he committed under duress (Rambam, Yesodei HaTorah 5:4). Rather, he would have violated the mitzvah of sanctifying G-d's name. Not being able to withstand the threat of death or untold pain is an understandable, if not acceptable, reason for violating the basic tenets of Judaism.

The Gemara's response is illuminating. "Rav Samma the son of Rav Assi said to Rav Ashi--and some say [that] R. Samma the son of Rav Ashi [said] to Rav Ashi--'Do you not make a distinction between a beating that has a limit and a beating that has no limit?'" It is understandable that one would choose death over pain, if that pain had no known end. But if the pain is only temporary, i.e., 39 lashes, such pain is preferable to death.

[1] The Meshech Chochmah, in a most beautiful and relevant piece, explains that oftentimes, the importance of mitzvoth must take into account social and historical factors such that a mitzvah that, on a technical level, is less important may, at certain times, take on a much more important role.