How common it is for people to return from a funeral and realize how little they knew about the deceased. All too often, it is only after a person’s death that one realizes the tremendous contributions made by the deceased. Alas, at that point, it is too late and we soon tend to return to our daily activities.

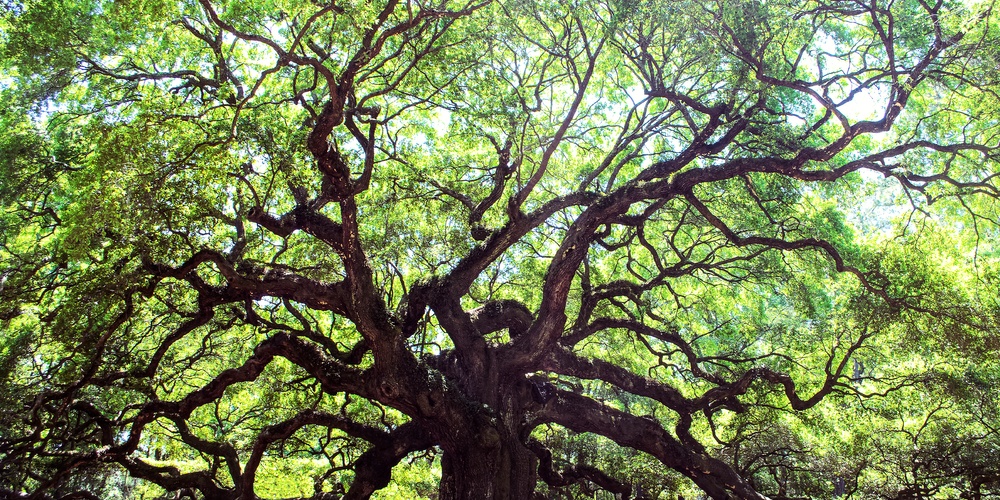

“And Devorah, Rivka’s wet-nurse, died and she was buried below Beit-El under the oak, and he [Yaakov] called its name the oak of weeping” (Breisheet 35:8). Devorah must have been a remarkable woman, so remarkable that the Torah interrupts its narrative to report her death.

Here was a woman whose death caused the shedding of many tears, a woman whose impact was such that they named the city of her burial in her honour. Yet remarkably, it is only at the point of her death that we are made aware that she even lived. Only at death was her cloak of anonymity removed. “And they sent Rivka, their sister, and her (unnamed) wet nurse, and the servant of Avraham and his men” (Breisheet 24:59). Apparently, Avraham's (unnamed) servant not only succeeded in finding a wife for Yitzchak, he also found a servant to accompany the new bride.

Avraham’s servant had told Rivka’s family that “G-d blessed my master exceedingly...He has given him flocks and herds, and silver and gold, and servants and maidservants” (Breisheet 24:35). Clearly, Rivka had no need to bring someone to help her, as she was set to establish her new home. Rather, her anonymous maidservant was an integral part of her life, and Rivka wanted her to accompany her to a strange land.

Devorah must have played a key role in the raising of Yaakov; how else to explain his tears upon her death? It was Devorah who, behind the scenes, was the glue that held the family together.

Rashi notes that Rivka had sent Devorah to tell Yaakov to come home—fulfilling a promise she had made many years earlier (Breisheet 27:45). Devorah’s death in transit symbolized the fact that the family would not be reunited. And so it was to be. While the Torah records in great detail the reunions of Yaakov and Eisav, and Yaakov and Yosef, no such reunion would occur between Yaakov and his mother. The last image Yaakov was to have of his mother was of her sending him away “for a few days” (Breisheet 27:44).

Remarkably, the death of Rivka is not even recorded in the Torah.

Our Sages note the mention of Devorah’s death is an allusion to the death of Rivka who, they claim, died at the same time. While from the perspective of Jewish history, Devorah’s role is minimal, from the perspective of the family it was crucial. And it is the death of Devorah, and not Rivka, that the Torah chooses to highlight. It was Devorah who allowed Yitzchak and Rivka to pass on the tradition of Avraham and Sarah to Yaakov and his family.

With Devorah’s death, the family begins to unravel. Soon thereafter, Rachel dies and Yaakov is left to care for his thirteen children, apparently alone—Leah is never heard from again. Yaakov finally reaches home, and immediately[1] thereafter is faced with the task of burying his father. The Torah records no crying by the family upon the death of Yitzchak, recording his death in an almost detached manner, lacking all emotion. Yaakov seems to have had a greater emotional attachment to his “nanny” than to his parents. This is not at all surprising when one considers the fact that it was his parents—each for their own reason—who ordered him to leave home. They had chosen favourites amongst the children, and it was his mother’s urging Yaakov to deceive his father that led to Eisav’s enmity towards him[2].

The Torah then digresses with a long list of the descendants of Eisav, only to pick up again with the tragic story of Yosef—one that split the family for so many years. The idyllic life of the young wet-nurse caring for Yaakov is no more than a distant memory as Yaakov is a broken man, mourning for his beloved son.

While the Talmud suggests that a person must strive to reach the heights of our patriarchs and matriarchs, precious few can dream of doing so. Yet we can all play the role of Devorah—provided we are willing to live in anonymity, offering the support needed so our leaders can effectively inspire the Jewish nation. Without the Devorahs of this world, we would be unable to produce the Rivkas and Yaakovs. We may not attain fame during our lifetime, but from the perspective of the Torah, our name will live on for eternity.

[1] In actual fact, his death took place many years later, some 12 years after the sale of Yosef. Yet there is no recorded conversation between Yitzchak and Yaakov, with the only recorded "coming together" of father and son being at Yitzchak's funeral. As with Terach and Avraham, the relationship between Yitzchak and Yaakov came to an end long before Yitzchak died.

[2] This could also be a result of Yitzchak and Rivka moving to Gerar soon after the sale of the birthright. The Torah tells us they were there for a long time, yet makes no mention of them having taken their teenaged children with them when they moved. The simple reading of the story itself would seem to indicate that they moved alone. If so, we can readily understand why Yaakov may have felt somewhat distant from his parents—and possibly why he never contacted them all the years he was in Lavan’s home.