The story of the slavery and subsequent redemption of the Jewish people focuses almost entirely on Moshe, Aharon and Pharaoh. Strangely, the thoughts, feelings, and actions of both the Egyptian and Jewish people are barely noted. Although we are privy to the suggestions of Pharaoh's advisors throughout the plagues, we hear nothing of the reaction of the populace. Did they support Pharaoh’s intransigence? Did they see the plagues as the hand of G-d? Did they even know that Moshe had forewarned them about the plagues?

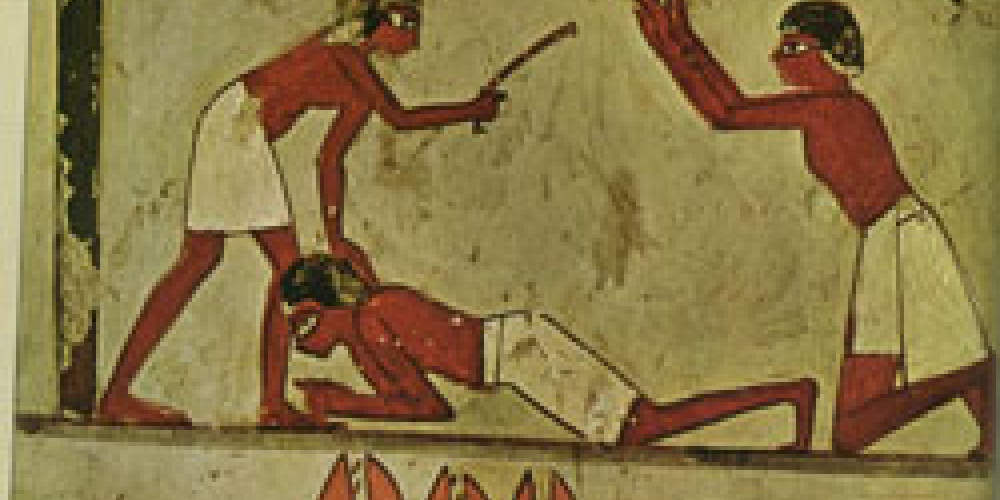

All we need to know about the Egyptian people is encapsulated in the verse, “The Egyptians started to make the Israelites do labor designated to break their bodies” (Shemot 1:13). The Torah passes its moral judgment on the Egyptian people; all else is superfluous. It is only during the last plague that we see the reaction of the people: “There was a great outcry since there was no house where there were no dead” (12:30). Moral lapses often bring severe consequences.

Similarly, we are told very little about the reaction of the Jewish people to the negotiations between Moshe, Aharon and Pharaoh. Did they see the hand of G-d and realize their redemption was near, or did they just want to be left alone? Were they even aware of the ongoing talks between Moshe and Pharaoh?

The Torah subtly points at a fundamental change that overtook the Jewish people. When G-d first appeared unto Moshe and appointed him His messenger to redeem the Jewish people, Moshe doubted the willingness of the Jewish people to follow him on such a historic mission. “But they will not believe me, they will not listen to me, they will say, G-d did not appear to you” (4:1). However, Moshe had underestimated the pure faith of the Jewish people. “The people believed. They accepted the message that G-d had granted special providence to the Israelites and that He had seen their misery. They bowed their heads and prostrated themselves” (4:31).

After 210 years in Egypt, the Jews could feel the approaching end of the exile, and looked forward to being able to “celebrate a feast unto Me in the wilderness” (5:1). Yet this initial wave of hope soon dissipated. After Moshe’s initial, unproductive meeting with Pharaoh, G-d told Moshe to relay to the Jewish people the news that they would soon leave Egypt, receive the Torah and settle in Israel. By the time Moshe did so, hope had turned to despair. “Moses related this to the Israelites, but because of their short spirit and hard work, they would no longer listen to him” (6:9). What happened?

After Moshe and Aharon asked the Egyptians to end their subjugation of the Jewish nation, Pharaoh ordered his taskmasters to “make the work heavier for the men, and make sure they do it. Then they will stop paying attention to false ideas” (5:9). A little setback, a few hardships, and suddenly their hopes were dashed! No further effort would be made by them to ameliorate their situation. Like many in difficult situations, they had learned to cope, and were unwilling to challenge the status quo lest their conditions deteriorate even further.

Tragically, this inability to see beyond the problems of today became the norm. In fact, the next time the Torah brings us the collective voice of the Jewish people, it was at the shores of the Red Sea. Instead of acknowledging the great miracles wrought on their behalf, they proclaimed, “Weren’t their enough graves in Egypt? Why did you have to bring us out here to die in the desert?” (14:11). Unfortunately, Moshe was correct when he stated, “even the Israelites will not listen to me; how can I expect Pharaoh to listen to me?” (6:12).

Such an attitude is understandable for a group of slaves. It is the consequence of slavery. People robbed of their dignity and freedom to choose cannot be expected to see beyond the problems of today.

The tragedy is when people who are physically free exhibit the same tendencies. So often, plans of great vision are shelved because of a few setbacks. Worse, some are not even attempted due to fear of failure or general apathy. Our spirits are broken much too easily. Yet truly free people know that “the only free person is one who engages in Torah”. Difficulties, obstacles, naysayers, and lack of funds are challenges, but they must not serve as barriers to the implementation of our Divine mission. After all, they are no match for Torah.