"Eino domeh shmiah l'rei'ah, one cannot compare hearing to seeing". I write these words at the end of our first day of the TiM trip to Poland. Seeing what I have spent a lifetime learning about offers a new and deeper perspective.

When we hear Poland, our instinctive reaction is to think about the Holocaust and the murder of 3 million, 90% of Polish Jewry. Many people told me that they would not, could not go to Poland. I fully respect and understand such emotions--yet, speaking for myself, there is no greater inspiration than seeing the places where the greats of our past lived, taught, and died.

Over the next week or so, I hope to share some--and they are just a very few--of my thoughts as we travel through Poland. And while I hope they are meaningful for you, as they are for me as I write them, I recognize that eino domeh kriah l'rei'ah. One cannot compare reading about something to seeing it.

As I discussed with Rabbi Dr. Shalom Berger, our scholar in residence (who so beautifully blends knowledge and emotion, the brain and the heart), as we planned the trip, this is not just a Holocaust trip. While so central and painful to Jewish life, we are here to see, as well as gain strength and inspiration from 1,000 years of Jewish life, much of it amongst the most wonderful period of the long years of Jewish exile. As Dr. Shalom noted, when one opens a page of the Shulchan Aruch, with the exception of the mechaber, Rav Yosef Karo, every person on the page lived and learned in Poland--from the Remah to the Shach and Taz, and even all the way down to the Mishnah Berurah. Poland was the cradle of Chassidut and the center of Jewish life for many years.

We spent the day in Warsaw. Had we visited 80 years ago, we would have been amongst 350,000 Jews, over 33% of the population of the city. It was the second most populous Jewish city in the world (after New York), and without a doubt, the city where Jewish life pulsated like no other. Here you had shteiblach by the hundreds, if not thousands, with its wide array of Chassidic courts, beautiful shuls, flourishing yeshivot, members in the Polish Sjem (parliament) from Agudath Yisrael, Zionists of all shapes and flavours, Bundists, Socialists, flourishing Yiddish theatre and newspapers, and everything else that made up the Jewish people. While tragically, it exists no longer, we are its heirs, who gain strength from our past as we guarantee our future.

We started our day with shacharit in the Nojek shul, the only remaining shul in Warsaw. Donated by the Nojek family, as a way to perpetuate their family name as they had no children, it was initially situated within and as the ghetto shrunk just outside the ghetto walls. It was used by the Nazis as a stable during the war which explains its survival. (Almost all of the city of Warsaw was destroyed during the war, and there was even talk of letting the city remain in ruins). Next to the shul is the community centre and not too far away is the Jewish day school, which today has some 250 students. It is led by a native of Poland who was sent to rabbinic school at Yeshiva University, enabling him to return to serve his community.

Most of our day was spent in the cemetery--a cemetery like no other in the world. Established in 1806, by 1939 over 150,000 Jews were buried there, with thousands more, first individually and then sadly many more added in mass graves during the war. While many of our cemeteries are the model of conformity, with strict rules as to size and placement of tombstones, the variety of style, shapes and sizes, and types of inscriptions--both written and "pictures"--of the tombstones was astounding, and gave one a real flavour of Jewish life in Warsaw. The towering trees, in full bloom and beauty in the summer months, that cover the hundreds of thousands of tombstones covey the message of life and growth even in a place of death. But it is the range and diversity of the people who are buried here--many famous and most not--that is so inspiring. Most, thankfully, lived full lives, raising families and generations of Jews.

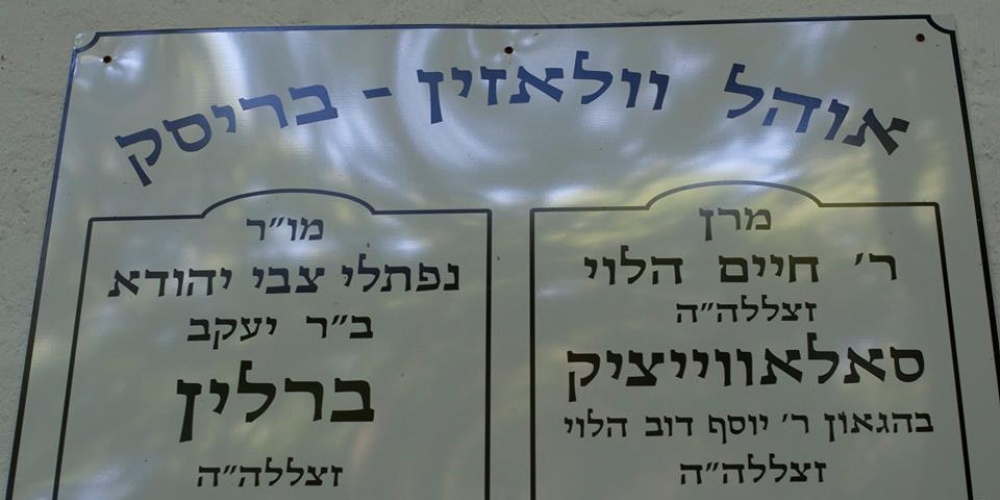

Let me just briefly mention three of the graves we saw. Buried side by side are the Netziv--Rav Naftali Tzvi Yehuda Berlin, the great Rosh Yeshiva of Volozhin who moved to Warsaw in 1892 (stopping on his planned aliyah to Israel to raise money to pay off the debts of the yeshiva) and died a year later--and his granddaughter's husband, Rav Chaim Soloveitchik who, as his tombstone records, was first and foremost Rav Hachesed, the rabbi of kindness. It was Rav Chaim who taught that the primary role of a rabbi is not to teach Torah (and there were none who reached his level as a teacher of Torah), but to care for the widow, the orphan, and the poor.

Not far from their ohel was that of the Modezter Rebbe, a Chassidic dynasty famous for its many niggunim--which if I am not mistaken include the classic Eishet Chayil and Mizmor LeDavid we all sing. Standing by his grave, Dr. Shalom recounted the story of how the Rebbe's student, Azriel David Fastag, composed the haunting melody of Ani Maamin in the cattle car as he was being deported to his death in Treblinka. Two people volunteered to jump from the train to bring the tune to the Rebbe--one of whom who survived the jump and succeeded in his mission.

With tears in our eyes--and tears as I write this--we sang Ani Maamin together, affirming our unwavering faith in the coming of the Mashiach.