“Moshe received the Torah at Sinai and transmitted it to Yehoshua, Yehoshua to the Elders, and the Elders to the Prophets, and the Prophets to the Men of the Great Assembly. They said three things…”

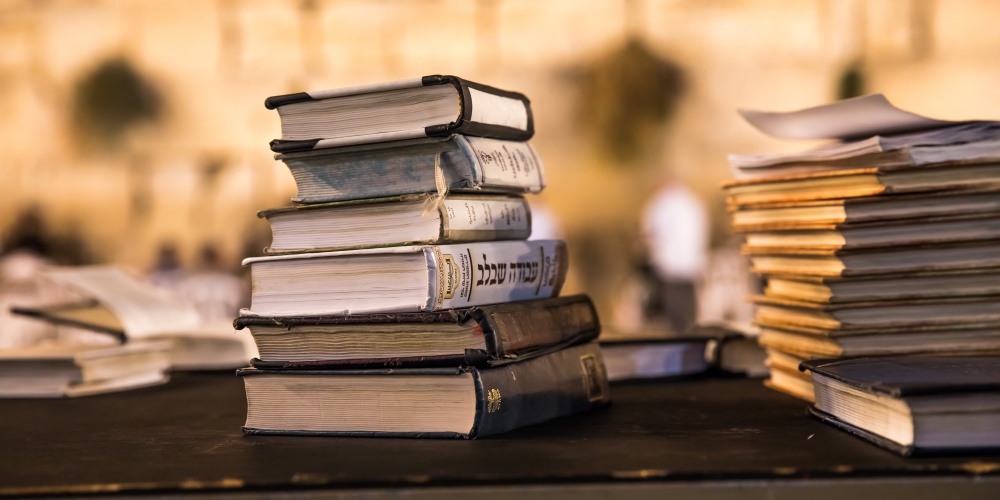

Pirkei Avot details the transmission of our mesorah, heritage, from the time of Moshe through to that of Rebbe Yehuda Hanasi, the final editor of the Mishna and beyond[1]. There is no need to quote any of the teachings of Moshe, Yehoshua, the Elders or the Prophets as their teachings are recorded in Tanach. However, soon after the building of the Second Temple the canonization of the Bible was completed and hence the need to record the teachings of those who followed beginning with the Men of the Great Assembly. As it would be another 700 years before permission was given to write down the Oral Law, the teachings were transmitted orally from teacher to student helping to ensure the vitality of the tradition.

This Mishna chronologically records the links in the chain of tradition through to the fourth Mishna of the second chapter. The period of the Anshei Knesset Hagedolah comes to a close with Shimon Hatzadik in the mid-4th century BCE. It was he who passed the tradition to Antichnus Ish Soco. It was then passed down to the zugot, the five pairs of co-leaders of the Jewish people, the Nasi and the Av Beit Din. This unit spanning from the Maccabean period through the turn of millennium begins with Yossi ben Yoezer and Yossi ben Yochanan and ends with Hillel and Shammai.

Before noting the actual teachings of these five pairs of Sages, the Mishna begins by stating the name of the particular Sage followed by the words “kiblu mehem, “received from them” i.e. the previous generation. We thus read, for example, “Hillel and Shammai received from them [Shemaya and Avitilon]. Hillel says…”. The primary function of our Sages is to receive the tradition from one’s teachers and to pass it down to one’s students. Only after relaying this seemingly superfluous yet vital information does the Mishna then list each of the teachings of these 10 Sages. These mishnayot thus serve a dual function; they list the main transmitters of the mesorah in each generation followed by their actual teachings.

We then move from the zugot to the Tannaim, the primary teachers of the Mishna taking us from early in the first century CE to the early third century. We hear of the teachings of Rabban Gamliel and his son, Rabbi Shimon ben Gamliel, continuing in the second chapter Rebbe [Yehuda Hanassi] who edited the Mishna, and finally Rabban Gamliel the son of RebYet the phrase kiblu mehem has gone missing. We have the teaching of the Nasi of each generation but the link to the previous generation is no longer mentioned. This is not by chance.

Beginning with the generations after Hillel and Shammai there was no longer one tradition. One could no longer pass down “the” tradition, but only “a” tradition, one that may be quite different from one’s neighbours. “From the time that the disciples of Shammai and Hillel grew in number, and they were disciples shelo shimshu, who did not attend to their masters to the requisite degree, dispute proliferated among the Jewish people and the Torah became like two Torot” (Sanhedrin 88b).

Sadly, Beit Hillel did not learn the importance of shimush, serving, their teachers from Hillel. “Is there any person who knows whether the Paschal lamb overrides Shabbat or not?” (Pesachim 66a). It had been many years since erev Pesach had fallen on Shabbat and the priests in the Temple were unsure if the korban pesach could be brought on Shabbat[2]. “They said to them: There is a certain man who came up from Babylonia, and Hillel the Babylonian is his name, shimesh, who mesamesh served, the two great scholars of the generation, Shemaya and Avtalyon and he knows whether the Paschal lamb overrides Shabbat or not” (Pesachim 66a).

Precisely because Hillel properly served his teachers, the tradition was preserved. And because he properly served his teachers “they immediately seated him at the head and appointed him Nasi over them. Because the students of Hillel (and Shammai) did not do so, the tradition splintered – there are over 300 between Beit Shammai and Beit Hillel alone – and the Torah became like two Torot[3].

Is it any wonder that Rabbi Yochanan said in the name of Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai: Service of Torah is greater than its study” (Brachot 7b).

[1] The famous Mishna of Yafeh Talmud Torah eem derecho eretz is taught in the name of “Rabban Gamlilel the son of Rebbe Yehuda Hanasi”. Either Rebbe included a teaching of his son in compiling the Mishna or this was a later addition to the Mishna.

[2] While communal sacrifices were allowed on shabbat, private ones were not. It was not clear if the korban pesach should be considered a private korban being an obligation on each individual Jew. Or perhaps since each and every member of the community had to bring it – and it was through the korban pesach we became a community - it should be considered a communal sacrifice and override shabbat.

[3] This teaching seems to conflict with the teaching that the teachings of both Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai are “words of the living G-d” (Eiruvin 13b). Whether they can be reconciled is something we will PG discuss at a future date.

Points to Ponder #3

***Our tradition equates a zaken, elder, with a chacham, the wise, and is clear from the opening there is a clear distinction between a zakena and a navi, each flourishing in different historical periods. Why can’t these two periods co-exist? What are the differences between the role of a prophet and that of an elder and what historical circumstances make each necessary? Was the total cessation of prophecy at the beginning of the second Temple period actually a blessing?

***How does one serve a teacher? Can one serve Rabbi Google who today may be the most popular rabbi in the world? What is the impact on the teacher-student relationship and on the development of our tradition as more and more people turn to “Rabbi Google” with their questions?