The most repeated mitzvah in the Torah—and hence, one can argue, the most important message of the Torah—is to be kind and sensitive to strangers, ki[1], because you were strangers in the land of Egypt. Over and over—somewhere between 36 and 46 times (Bava Metzia 59b)—the Torah stresses this message[2]. Collectively, the Jewish people know full well what it means to be strangers, whether through outright hostility or more subtle forms of discrimination. We dare not do that to others. We can be proud that throughout our history, many Jews led and continue to lead the battles for the immigrant, the oppressed and the excluded—provided that we do the same.

While our sensitivity to the stranger is rooted in our historical experience, our sensitivity to the poor should be rooted in basic human decency. And it is sensitivity to the poor that takes centre stage on Pesach.

We who live in the West, in the most prosperous time in history, in countries with wide social safety nets, often think of the poor as those who drive a beat-up car, can’t afford vacations, or rent an apartment instead of owning a home. How fortunate we are. While there is much greater poverty than most realize—one in nine people in Toronto live below the poverty line[3]—the poverty line is much higher than it once was. Many of those considered “poor” today have amenities that would have placed them among the wealthy of the medieval period. Unlike the great Irish potato famine, in which over one million people died, there is no lack of food in the West, even as it is not always readily available to all and too many suffer from malnutrition.

For most of human history, and sadly, still today in many parts of the world, hunger was and is of serious concern, leading to much suffering and death. It is not by chance that the Rambam rules that, "We must be especially careful to observe the mitzvah of tzedakah, more so than any other positive mitzvah" of the Torah. More than shofar, mezuzah, or tefillin and of course, more than matzah. It is, as the Rambam notes, “the sign of the righteous descendants of Avraham” (Hilchot Matanot Anieem 10:1).

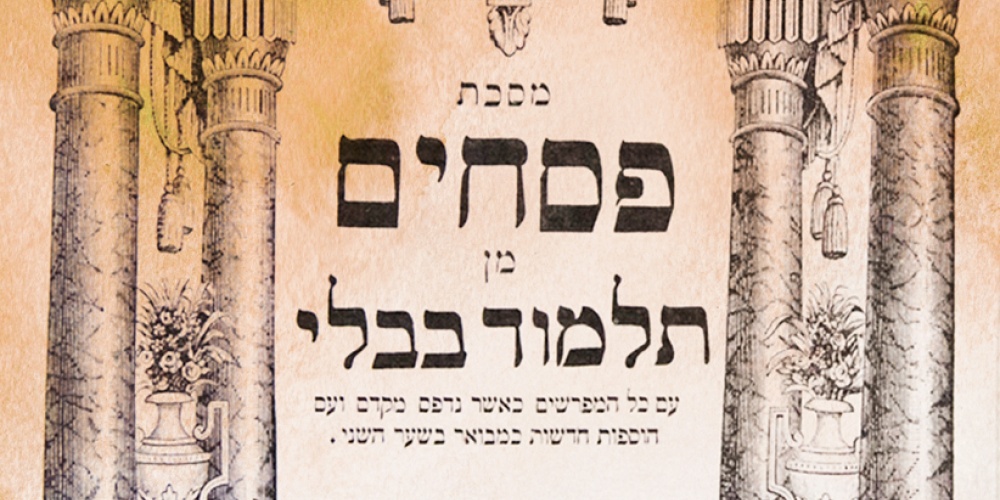

Yet with Pesach the time to celebrate our freedom, the masechet begins by depicting great wealth. “And why did they say two rows in the wine cellar?” (Pesachim 2a). The opening Mishna discusses the law of bedikat chametz, the search for chametz, noting that one need only search for chametz in places where chametz might be found. Those wealthy enough to have a private wine cellar and a butler at their service must be concerned that the butler may have accidentally dropped some bread in the wine cellar. Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai disagree regarding the extent to which the wine cellar must be searched for chametz. This is a nice debate for the seriously wealthy, but of little concern to most.

With great wealth comes great responsibility. The opening vignette[4] contrasts with the opening Mishna of the tenth and concluding chapter of Pesachim. Here, too, the discussion focuses on wine, but in a much different context. “And they must not give [him] fewer than four cups of wine, even [if they need to take] from the tamchui, the charity plate” (Pesachim 99b). The tamchui is the charity plate for the poorest of the poor, with only those who do not have enough money for the next two meals allowed a tamchui distribution. That funds from the tamchui plate would be used to pay for four cups of wine for the indigent flies in the face of standard Jewish law, where one is commanded “to make their Shabbat a weekday”—i.e., eat two meals instead of three—rather than ask for charity. But Pesach is the holiday when every Jew must be treated like royalty, and that includes having four cups of wine. And before one sits down to eat, one must ensure that even the poorest of the poor can feast like a king, even if only for a night.

How appropriate that the halachot, laws, of drinking wine on Pesach begin with the obligation to ensure that the poor, too, can enjoy four cups of wine. Even an introductory line that all must drink four cups of wine is absent. The Mishna gets right to the bottom line with the admonition to give not less than four cups of wine to the poor. It is through the obligation to give to the poor that we first learn of the mitzvah to drink four cups of wine on Pesach.

In a similar vein, the opening words of the RaMaH in Hilchot Pesach are in reference to maot chitim, the requirement to ensure that the poor are provided with their Pesach needs (Orach Chaim, 429:1).

While the specific details may be unique to Pesach, the concept is not. Masechet Shabbat opens with the case of a wealthy homeowner providing food for the poor (homeless?)[5]. Our special days are special to the extent that we ensure that we have taken care of the needs of the poor. The words of the Rambam make this perfectly clear.

“While eating and drinking, one must feed the stranger, the orphan, the widow, and other poor unfortunates. Anyone, however, who locks the doors of his courtyard and eats and drinks along with his wife and children, without giving anything to eat and drink to the poor and the desperate, does not observe a religious celebration but indulges in the celebration of his stomach. And about such is it stated (Hosea 9:4), "their sacrifices are like the bread of mourners, all who eat it will be impure; for their bread is for their own appetites." Such joy is a disgrace for them, as it is stated (Malakhi 2:3), 'I will spread dung on your faces, the dung of your festivals'" (Rambam, Hilchot Shiveetat Yom Tov 6:18).

[1] In Biblical Hebrew the word ki has at least four possible meanings: if, when, because, and despite. In our context, in addition to because, the word ki can also be understood to mean despite, so that the Torah is warning us that despite the fact that we were strangers in Egypt, we should not mistreat others. Sometimes those who have endured pain and suffering are the least sensitive to others, feeling that if they suffered and “survived”, others can do the same.

[2] See here for an attempt to actually list these places and here for my referenced article on the subject.

[3] Contrary to what many think, the numbers are little different for the Jewish community. Just as the all-too-many who think alcoholism, gambling, spousal abuse and more are somehow a problem only in the non-Jewish world are mistaken, the same is true regarding poverty. In fact, while the timeline may not completely match, one in eight Jews in the city of Toronto lived below the poverty line (see here), a number that compares unfavourably with the one in nine of the general population of Toronto.

[4] Interestingly, the Mishna makes no mention of a butler, that being an addition by Rashi. Perhaps he assumed that the homeowner would be careful not to enter the wine cellar with bread precisely to avoid having to check it, something that may of little concern to the (non-Jewish?) butler. Or perhaps Rashi, in the spirit of Pesach, wanted to highlight our royal status. After all, the custom is to have others pour us the wine at the seder.

[5] See our brief discussion here where we note that had the homeowners actually invited this poor (possibly homeless) person into their home, they would have avoided the desecration of Shabbat.