Adam and Eve, Noach and his anonymous wife, Abraham and Sarah (and Hagar), Yitzchak and Rivka, Yaakov and his multiple wives, Moshe and Tziporah, all had one thing in common: they all had great difficulty raising children. Many--in some cases, most--of their children left a most negative legacy. It is as if the Torah wants to highlight the difficulty of raising children, something that is both somewhat depressing yet at the same time, most encouraging. We cannot expect to bat 1.000 when even Abraham had only one of his eight children follow in his footsteps, and yet he is the founding father of our people.

"Moshe commanded us the Torah, a heritage to the Congregation of Jacob" (Devarim 33:4). The primary function that we as Jews have is to transmit the Torah from one generation to the next. This is done, first and foremost, by being a role model for others. This is an obligation we all share and, while it is most "easily" done by raising our own children, even those with no children share this obligation. "So says G-d to the barren ones who observe my Shabbat, and choose that which I desire, and grasps My covenant tightly: I will give them in My house, and within My walls, a place and a name (Yad v'Shem), better than sons and daughters, eternal renown I shall give them" (Isaiah 55: 4-5).

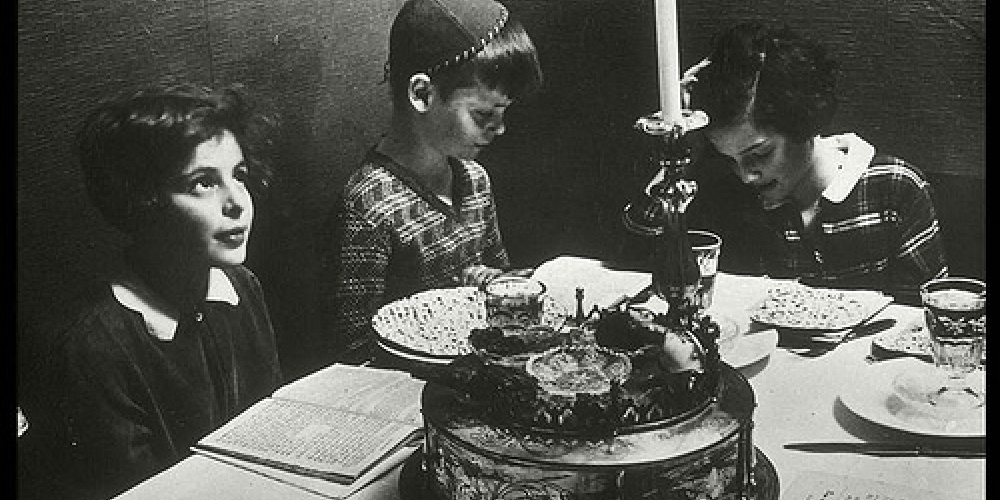

We are most cognizant of our roles as transmitters of our heritage on Pesach; as our foundational holiday, it focuses on children-they being the guarantors of our future. And at every seder, our tradition asks that we welcome four children. Once again we highlight the difficulty of properly raising children, as only one of the four is what we would call a model child. Very few of us want to raise a rasha or a tam. Worst of all is to have an apathetic child who does not even care to ask.

While much of what happens to the next generation might be beyond our control, much of it is not. Our Sages were not hesitant to find fault with some of the practices of our founding families. Yitzchak and Rivka committed the two cardinal sins of playing favorites and not recognizing the differences between their children (See R. SR Hersch Breisheet 25:27). Yaakov followed suit, and our Sages note, "because of a special coat Yaakov made for Yosef, the brothers were jealous, leading to the descent of our ancestors to Egypt" (Shabbat 10b).

Many have noted that there is little to distinguish between the questions of the wicked and the wise child. There often is a very fine line between wise and wicked. The Rambam (Teshuva 3:1) defines a rasha as one whose actions are composed of 49.9% mitzvoth and 51.1% aveirut, (sins) with a tzadik having 51.1% mitzvoth versus 49.9% aveirut, a slim difference indeed.

The Torah introduces the question of the chacham with one key word not found by the other children. "When your child will ask you machar, tomorrow" (Devarim 6:18). "Who is wise?" our Sages ask (Tamid 32a). "One who sees what will be born" i.e., the impact of one's actions today on tomorrow. When we raise our children so that tomorrow, they will ask questions--tomorrow, they will be involved members on our community--we have raised a wise child.

Like so much and so many in our society, the rasha and his siblings are focused on today, ignoring the impact on tomorrow. This focus on today is the mindset that we find in politics, in business (with its obsession with quarterly profits), in lifestyle choices, and so much more. Thechacham is focused on the long-term, and makes choices today to ensure the viability of tomorrow.

Rav Soloveitchik beautifully explains that the dispute between Yosef and his brothers revolved around the ability to see the changes in society that were just around the corner. The brothers wanted to follow in the pastoral ways of their parents, while Yosef urged them to note that as the world was changing, they must also change. A similar dispute, the Rav notes, played out in the reaction to Zionism, with many too slow to realize that a new world was replacing the old. As the Rav notes, G-d voted for Yosef.

Children are pure, naïve and innocent. But unfortunately, they do not remain that way for long. It is the messages we send our children--both direct and, perhaps even more importantly, the subtle messages we send--that determine what they will do tomorrow, when they mature and go out on their own.

Our generation is the most successful generation since the emancipation at maintaining Jewish commitment in our youth. Yet at the same time, there are growing numbers who care little about the future of Judaism, even as they may attend a seder and be passive members of our community. It is our task to demonstrate the relevance of Judaism, inspiring others to be passionate members of our community, and guaranteeing that tomorrow, our children will continue to ask the most important questions of the day.