One of the most well-known Talmudic passages of masechet Megillah is the teaching of Rava that “one is obligated l’beshumei, to drink, on Purim, until one does not know the difference between cursed Haman and blessed Mordechai” (Megillah 7b). Despite the embrace of so many of this idea, it is debatable whether this teaching of Rava is actually accepted. The Gemara follows this teaching with a story of how one year Rava’s teacher, Rabba, invited Rav Zeira to join him for the Purim seudah. They had much to drink (clearly too much), and Rava “arose” and “slaughtered” Rav Zeira. The next morning—apparently after having sobered up—Rava “pleaded for mercy”, and Rav Zeira was revived. The following year, when Rava invited Rav Zeira to once again join him for the Purim seudah, Rav Zeira declined the invitation, telling Rava, “Not every day does a miracle happen”.

The juxtaposition of these stories led a number of commentaries to argue that Rava’s teaching is to be rejected. While mainstream halacha does accept the view of Rava, that does not mean one may drink to excess. For example, the RaMaH (Orach Chaim 695:2) explains that one should drink a just enough to get tired, go to sleep and while sleeping one will not know the difference between Mordechai and Haman.

There is no citation necessary to demonstrate that getting stone drunk is forbidden. I am reminded of the story quoted by Rav Zevin in the wonderful book, Ishim V’shittot, where he paints illuminating portraits of the unique contributions of ten great Torah scholars of the 19th and 20th centuries. In his discussion of Rav Chaim Soloveitchik, he recounts how someone once quoted an opinion in the name of the Tosafists. Rav Chaim immediately responded that Tosafot say no such thing. When asked if he knew every single Tosafot, he replied, “No, but I know Tosafot could never say such a thing”.

To imagine that Jewish law would allow one to drink oneself into a stupor is plainly and simply unimaginable. Regarding hunting, the Nodah B’Yehuda writes that, while he cannot find a technical prohibition to hunt, the fact that the first two hunters we meet are Nimrod and Eisav tells us all we need to know. A similar argument can be made regarding getting drunk. The Torah describes two instances of people getting drunk, Noach and Lot; and the stories do not end well.

Nonetheless, there is a mitzvah to drink on Purim[1]. But there is drinking and there is drinking. Rava tells us that we must l’bshumei on Purim. Rashi explains that it means we are to drink wine—and apparently the requirement is specifically wine. “Nichnas yayin, yatza sod, when wine enters, secrets escape” (Eiruvin 65a). And when secrets escape it can be very embarrassing. If such is the case, one should refrain from getting anywhere near this level of intoxication. But the ideal (and exceedingly rare) Jew is tocho k’boro, his inside is like his outside; or as we might say, what you see is what you get. There are no airs, shows, and pretense, and surely no hypocrisy. For such a person, drinking is a beautiful way to demonstrate that the inner essence of a Jew is pure. If one can reach such a level, there is much to celebrate and much to drink to.

Purim is the time to reveal that which is hidden. From Esther’s name to G-d’s missing name, Purim is the holiday where nothing is quite as it seems. What appears on the surface is overshadowed by the goings-on behind the scenes. “V’nahafochu, it is just the opposite”. What is hidden is the true reality, a perfect parallel to drinking in general. The Megillah describes no fewer than ten parties, and “the rule for the drinking was, ‘No restrictions!’ For the king had given orders to every palace steward to comply with each man’s wishes” (Esther 1:8). The Megillah appears to be a most secular book—but is anything but.

Just as eating can be a method of divine worship, with our table serving as an altar, or an animalistic act, so, too, with drinking. We can drink in order to escape reality, using alcohol as a way to avoid confronting our challenges; or we can drink “to gladden the heart” (Tehillim 104:15), bringing an extra dose of joy into our worship of G-d. One can drink like cursed Haman or like blessed Mordechai, and we dare not confuse the two. Yet doesn’t Rava teach that we should drink until we do not know the difference between the two?

Rava does not say we are to drink at all; instead, he says we are l’beshumei. While in context, it may mean to drink, why did Rava not say so directly? The word beshumei comes from the roof bsm, which means something sweet, or a type of spice—hence, the besamim, the sweet-smelling spice that helps us start a new week feeling refreshed. In the Megillah, the young maidens spent six months b’besamim, being anointed in sweet smelling oils. In the immediately preceding Gemara, Abaye, talking about himself, quotes a popular folk saying, one that is at least as insightful today as it was 1,700 years ago: “Ravcha l’b’sima shechiach, room for sweets can always be found”.

That the word b’sumei is related to sweetness and fragrances can be seen by examining the first time the word bosem appears in the Chumash.

"Where is Mordechai [hinted to] in the Torah, our Sages want to know?" (Chulin 139b). Our Sages quote a verse which details how the oil used to anoint the kohanim was to be made. “Take choice spices; mar-dror, five hundred weight of pure myrrh; kinamon beshem, fragrant cinnamon, half as much; u’k’ne bosem—two hundred and fifty—of fragrant cane” (Shemot 30:23). The Targum translates mar-dror as Meira-dechai, thus placing the "original" Mordechai as a priest in the Temple.

Yet Haman, too, is connected to sweetness. Where is Haman in the Torah, our Sages ask in the same Talmudic passage? Using a play on the words hameen and haman—and with no vowels in the Torah, they are spelled the same—our Sages quote G-d’s question to Adam in Gan Eden: “Hameen ha’eitz, did you eat of the tree from which I had forbidden you to eat?” (Breisheet 3:11). Unfortunately, they had. But why? “When the woman saw that the tree was good for eating and a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was desirable as a source of wisdom, she took of its fruit and ate. She also gave some to her husband, and he ate” (Breisheet 3:6). As the Sforno explains, Chava was attracted to the fruit because of its pleasant smell. She naturally assumed that with such a sweet fragrance, the fruit surely is “good for eating”.

While the sin of eating the forbidden fruit was the sin of Adam and Chava, our Sages saw in this sin the making of Haman. Just as Adam and Chava could not tolerate being able to eat every fruit except for one, so, too, Haman could not tolerate everybody bowing down to him except one old Jew[2].

Our commentaries have noted how the Mishkan is man’s attempt to recreate Gan Eden, to get back to G-d’s chosen place[3]. Gan Eden and the Mishkan are two avenues to the worship of G-d. Gan Eden focuses on the physical aspect of life and the Mishkan on the spiritual. In Gan Eden, there was no difference between them; hence, man could be naked, yet modest. Only with sin did we need to cover our bodies with clothes. Once expelled from the garden, the physical and the spiritual co-exist in a state of tension. It is difficult to worship G-d with the same intensity with our physical beings as with our spiritual.

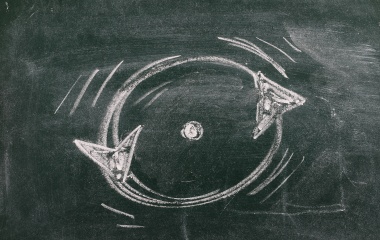

Difficult, but not impossible. We must aim to be able to worship G-d with equal fervor whether we are in Gan Eden, the “birthplace” of Haman, or in the Mishkan the “birthplace” of Mordechai. We must serve G-d whether we are in the executive suite or standing on the bimah. Is it any wonder that our Sages note that Yom Kippurim is Yom K’Purim, a day like Purim? On Yom Kippur, we leave the physical world, focusing on the spiritual; and on Purim, we leave the spiritual to focus on the physical. But the two days must be one, flip sides of the same coin, as we worship G-d throughout the year with both our physical and spiritual beings, with the power of both Haman and Mordechai, thus blurring the difference between “cursed is Haman and blessed is Mordechai”.

Our Sages teach that “the grandchildren of Haman studied Torah in B’nei Brak” (Gittin 57b). With hard work, Haman can become Mordechai, and the power of hate can be transformed to that of love. At that point, there will be little difference between Haman and Mordechai. Let us drink to that.

[1] It is very important to note that this mitzvah applies only during the Purim seudah. There is no mitzvah to drink outside of that framework. That does not mean it is prohibited—if done properly—but there is no mitzvah to do so.

[2] Others see the tree as the link between the downfall of Adam and Chava, and Haman.

[3] To cite just one example, G-d placed keruvim with swords at the entrance to prevent man from attempting to return to the garden. These keruvim next appear as the golden images that adorned the Aron Kodesh.