“And the Egyptians were burying all their first born, who had been killed by G-d” (Bamidbar 33:4).

Occupied with grief and despair, the Egyptians watched—apparently in silence—as their former slaves “left triumphantly before the eyes of all the Egyptians” (Bamidbar 33:3). Interestingly, neither the frantic burials nor the triumphant departure of the Jewish people is mentioned in parshat Bo, when these events actually transpired. Rather, “there was a great outcry, since there was no house where there was no dead” (Shemot 12:30), leading Pharaoh to order the Jewish people to leave to “go worship G-d, just as you demanded” (Shemot 12:31).

This technique of outlining a story, then filling in details later on, is a common feature of the Chumash. Specific details are revealed where they are most appropriate thematically, not necessarily when they actually occur. In Shemot, the focus is on the miraculous escape of the Jewish people and the fear that gripped all of Egypt that they, too, would die: “We are all dead men, they were saying” (Shemot 12:33). The aftermath of the burial of the Egyptian children is a side detail, not relevant to the miraculous events of the Exodus. In parshat Masei, however, it is the miraculous survival of the Jewish people in the desert that is celebrated, in contrast to the deaths and burials that engulfed Egypt.

This later filling-in of details also occurs in the narrative of the sale of Joseph, the story that began our descent into Egypt. Reading the story, we get the impression of a weak brother, ambushed and probably gagged as he was thrown into the pit; the voice of Joseph is nowhere to be heard. In parshat Vayeshev, the Torah is focusing on the sale of Joseph, and his voice has no bearing on our arrival in Egypt. It is only later, when the brothers were in jail and full of remorse for their actions, that we hear of their callousness as they “saw him suffering when he pleaded with us, but we would not listen” (Breisheet 42:21). The fact that they ignored his screams is just cause for their acknowledgment that “we deserve to be punished because of what we did to our brother” (Breisheet 42:21). Here, it is the personal cruelty of the brothers, not the national impact, which concerns us.

This phenomenon occurs a number of times in our parsha, but I will call your attention to just two incidents.

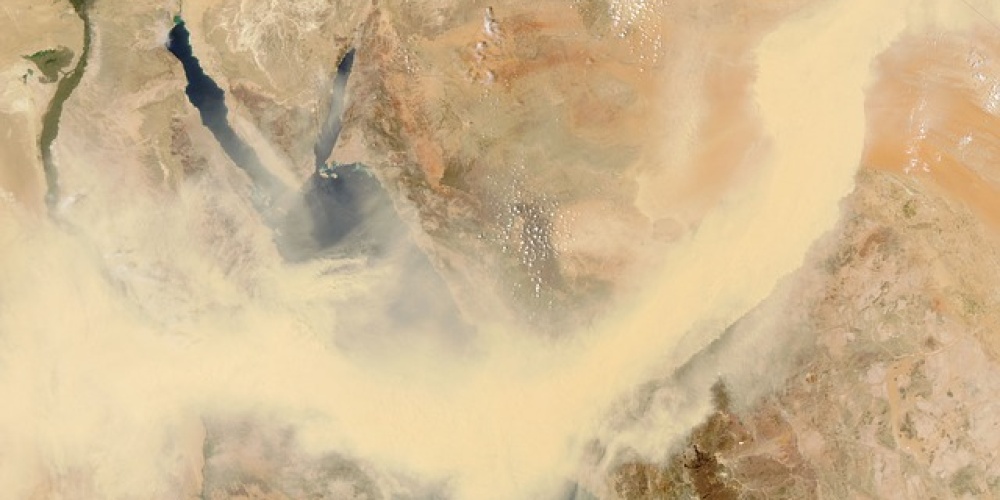

The parsha opens with a listing of the forty-two places in which the wandering nation encamped in the desert. Yet many are listed here for the first time. Places such as Dafka, Alush, Tarach, and Punon are only mentioned in this retrospective retelling of our journey in the desert. Sefer Bamidbar is not a chronicle of the wanderings of the Jewish people in the desert, and does not detail their every stop and start. Rather, it is a book that explains the failure of the Jewish people to fulfill their historic mission. Only those places that contributed to this failure are listed.

In parshat Masei, however, the theme changes; now the focus is on the preparations for entering the land of Israel. The Torah addresses the mitzvoth of settling the land, delineating the borders of the soon-to-be State. The command to set up cities of refuge to deal with some of the social problems that would undoubtedly be encountered is also recorded here. Masei contrasts the aimless meandering of the desert—all forty-two stops—to the permanent (it was to be hoped) settlement of the land of Israel. It is not the failures of the Jewish people but their miraculous survival, despite the long journey, that is alluded to by mentioning these otherwise meaningless places.

“Aharon the High Priest…died there on the first day of the fifth month. And he was 123 years old” (Bamidbar 33:38-39). The circumstances of Aharon’s death are detailed in parshat Chukat; yet it is only here that his date of death, Rosh Chodesh Av, is mentioned[1].

In parshat Chukat, Aharon’s death is connected to the way in which he and Moshe Rabbeinu somehow failed to sanctify the name of G-d when they got water from the rock. How old he was when he died and the exact date of his death were not relevant there. But as the Jewish people prepared for their entry into the land, the story of the death of Aaron serves as a subtle reminder that their right to live in the land is conditional. If the Jewish people follow Aharon’s lead and, like him, can be described as people who are ohev shalom v’rodef shalom, lovers and seekers of peace, then all will be well with them. If the Jewish people fall victim to internal discord, then the massaot, the heavy burden of wanderings, will restart, marooning the Jewish people in many more than forty-two places.

Aharon died as we entered the month of Av. Yet it is not the physical death of Aharon, as recorded in parshat Chukat, that we mourn here. Rather, it is his spiritual death, the death of his legacy of peace and harmony, which we mourn on the first of Av. Let us have the strength to love and seek peace so that the wanderings of the Jewish people can come to an end once and for all.

[1] Tellingly, Aharon is the only person in Chumash whose date of death is recorded. Such serves as a prophetic reminder that especially as we enter the month of Av it is Aharon's example that we must follow.