Portugal is one of the few countries in Europe in which no Jews were deported during World War ll. The only Portuguese Jews to be killed in the Holocaust were those who happened to be out of the country and were trapped in a country when the Nazis invaded. A plaque memorializing these victims sits in the shul courtyard of Lisbon. Antonio Salazar, the dictator who ruled Portugal from 1932-1968 maintained complete neutrality during the war. While he had positive relations with Hitler ym”s and had flags flown at half-mast upon his death, he did not allow a single Jew to be deported. Arriving in Portugal meant safety – but arriving here was no easy matter and it was very difficult to get a legal visa to enter the country.

Aristides de Sousa Mendes consul-general for Portugal in Bordeaux, France defied the orders of his superiors and issued some 30,000 visas to Portugal, with approximately 10,000 given to Jews, mostly during June 1940. This act of heroism earned him a suspension and eventual firing from the diplomatic service. His 15! children were not allowed to attend university – many eventually moving to the United States - and he died in poverty in 1954. In 1966 he was recognized by Yad Vashem as one of the righteous of the nations. Only in the 1980s did Portugal officially apologize to his family and the Portuguese Parliament promoted him posthumously to the rank of Ambassador. It was only in October 2021, less than one year ago, that he was honoured in a public ceremony and the unveiling of a statue in his honour in Lisbon.

Besides those who received visas, many but not enough people reached Portugal by managing to cross the border into Portugal. Two people on our trip are here only because their fathers managed to escape to Portugal and from there to America. The most famous Jew who escaped from the Nazis by way of Portugal was Menachem Mendel Schneerson, later to become the Lubavitcher Rebbe.

The Rebbe may have had to flee to Portugal but his followers have returned. In 2010 Rabbi Eli Rosenfeld and his wife Rivka arrived in Portugal – the last country in Europe that up to that point did not yet have a Chabad centre. They did not speak the language, basically knew no one (they had come previously on a summer pilot trip) but came on a mission. Visiting the Avner Cohen Casa Chabad Centre, a 50,000 square foot complex in the heart of Cascais, some 30 kilometers west of Lisbon confirms much success. They set up in Cascais as that is the area that has the greatest concentration of Jewish families in the area. More importantly, they are operating a summer camp with some 35 children, and are planning to open up an after-school program, for the purpose of “bringing in Jewish kids, giving them some kosher food and teaching a bit of Torah”.

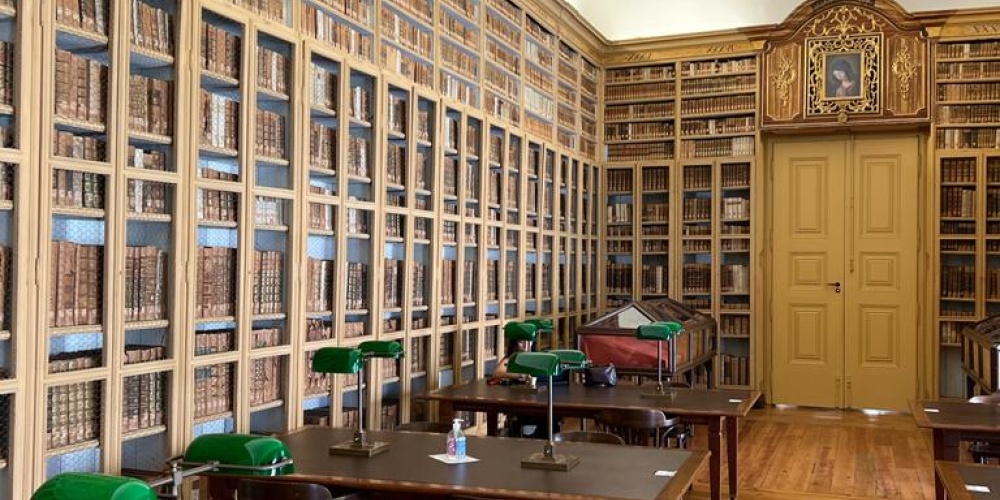

The library at Chabad has an impressive collection of books printed in Portugal and written by Portuguese rabbis over the years. Portugal was a centre for the printing of Jewish books at the end of the 15th century. The first book of any kind printed in Lisbon was the commentary of the Ramban on Chumash, a facsimile of which is housed in the library. One of the many fascinating books is an old edition of the Abarbanel – born in Lisbon in 1437 - on the Chumash, in which one can see the hand of the censor. One can clearly see how the censor took a marker to cover the the Abarbanel’s comment on the verse “among those nations you shall find no peace, nor shall your foot find a place to rest” (Devarim 28:65). But one can also see how the ink of the censor was of much lesser quality than that of the Abarbanel and the censors ink has mainly faded away allowing us to read the uncensored comment of the Abarbanel. He explains that no matter what the Jew does the non-Jew will always accuse him of trying to Judaize others and will torture us as they did to us in Spain. One can easily understand why the Abarbanel would write such and why the censor would try to censor it.

Despite the fame of the Abarbanel his commentary on the Chumash was first published in Venice only in 1579, some 71 years after his death. Of his many writings only three were published in his lifetime, the most famous being his commentary on the Haggadah. This was the first Haggadah printed with a commentary.

Like most great commentators he was an original thinker and one influenced by his times and experience. Seeing the evil of Ferdinand and Isabella firsthand it should not be a surprise that he had a very negative view of monarchy, claiming the Torah begrudgingly allows a monarch, a view in sharp disagreement with the Rambam. He had no compunction disagreeing with the Talmudic Sages regarding the authorship of the books of Nevi’im and Ketuvim. Based on the very different style of Sefer Devarim he raises the possibility that the book reflects Moshe’s own words and unlike the other books of the Chumash was not dictated by G-d. While he rejects that view the fact that he entertains it as possible is striking for those raised in the tradition of Maimonides. I imagine that those who find this type of approach open and modern would not say the same about Abarbanel’s claim that women are not created in the image of G-d, a view that was not unheard of in the middle ages amongst both Jewish and non-Jewish scholars, but I imagine that most today, even in the most insular of communities, would find offensive. This is another example of how we cannot judge people of the past based on the norms of today.

Rabbi Abraham Saba, a younger contemporary of the Abarbanel was one of the great preachers of Spain. Arriving in Portugal from Spain in 1492 he spent the following five years writing his thoughts. At the time of the forced conversion his children were forcibly taken away from him and baptized, and he fled from Porto to Lisbon with only the manuscripts of his writing. Upon learning of a death sentence for those owning Hebrew books, Rabbi Saba hid his manuscripts in an olive tree – never to be recovered. He was soon thereafter in 1497 expelled from Portugal[1] lamenting the loss of his children and his Torah which had offered some comfort. Living in Morocco he rewrote his books – as best he could from memory. As anyone who has ever lost even a Word document can attest, to re-write that which has been lost in extremely difficult – both intellectually and psychologically. His commentary on Chumash Tzror Hamor was extremely popular and the Chabad library has one of the early editions.

Rabbi Rosenfeld has made it his mission not only to collect these books but to focus much of his teachings on the scholarship of the great rabbinic teachers who hundreds of years ago lived in Portugal.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] As to why he was not forcibly converted, like almost all other Jews in Portugal, Dr. Shapiro, our amazing scholar in residence speculates that the Portuguese wanted to rid themselves of the leading rabbis fearing they may strengthen the resolve of the average Jew to remain steadfast in their Jewish practice.