"All korbanot mincha, flour offerings, are to be made of matza with the exception of the chametz of the korban todah, thanksgiving offering, and the shtei halechem, two loaves of bread [offered on Shavuot] that are made of chametz” (Menachot 52b).

That flour offerings may not be made of chametz is explicitly[1] stated in the Torah, not once but twice. “No meal-offering, which you shall bring unto the Lord, shall be made with leaven; for you shall make no leaven, nor any honey, as an offering made by fire unto the Lord” (Vayikra 2:11). “This is the law of the meal-offering…it shall not be baked with leaven. I have given it as their portion of My offerings made by fire; it is most holy, as the sin-offering, and as the guilt-offering” (Vayikra 6:7-10).

Yet despite the Torah’s unequivocal prohibition of offering a korban mincha containing chametz, in question after question the Gemara attempts to re-interpret the meaning of the verses and thereby allow the korban mincha to be brought even if it may contain chametz. Rav Chisda suggests that perhaps the prohibition does not apply if the leavening process has just begun (dough we would throw out when making matza for Pesach). Rav Nachman suggests that perhaps the prohibition applies only if the flour is baked into chametz, but that one can offer a korban mincha of chametz if it is boiled first (like a good bagel). Ravina suggests that perhaps it is prohibited for one to allow the korban mincha to become chametz, but once it does becomes chametz, there is no prohibition against offering it on the altar.

None of the above suggestions are accepted, and the Gemara’s response makes it quite clear that the verse means what it says it means—namely, that allowing a korban mincha to become chametz is strictly prohibited. In fact, the very next Mishna (Menachot 55a) teaches that one can violate the biblical prohibition of chametz three different times with one korban mincha: by kneading a dough of chametz flour, by arranging into its proper shape and by baking it.

Why—with the verse so clear and the Mishna’s unequivocal expression—do the Talmudic rabbis seek to apply the prohibition in a more limited fashion[2]?

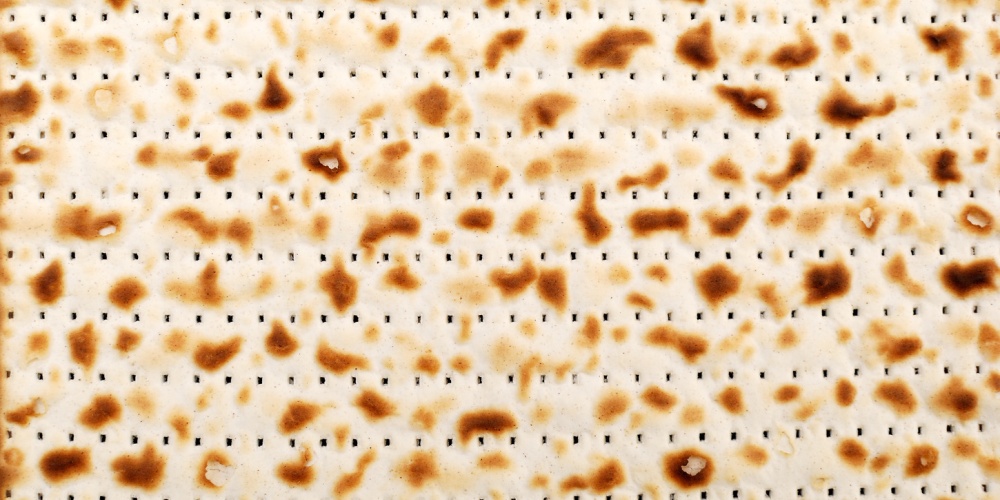

Matza is not a very tasty food. It is the food of slaves, lachma anya,”bread” of the poor. Could it really be that this is what we are meant to offer in the Temple, where no expense was spared to glorify and beautify it, where those who worked there had to have the most exquisite clothing? Matza just seems out of place in the Temple, and perhaps it is for this reason the rabbis sought (unsuccessfully) to somehow limit the prohibition.

This just begs the questions as to why the Torah forbids an offering consisting of chametz in the first place. The Sefer Hachinuch begins his discussion of this mitzvah with a disclaimer, noting that “the root of this mitzvah is very hidden, [making it hard] to find even a small hint [for its reason]”. Nonetheless, he continues by noting that since the goal of his writings is to inspire the youth, demonstrating that the laws of the Torah have meaning and purpose, he will write what came to mind. Knowing that many may find his reasons unsatisfactory, he pleads that “those who would object should not object after knowing my purpose”[3].

He[4] explains that the practice of sacrificing only matza serves to imbue within us the need to acquire the qualities of alacrity in the service of G-d. To make matza, one must work quickly with no time to relax, the same attitude needed in our service of G-d.

This is most debatable—all too often, the more people involved, the less that gets done—and the Sefer Hachinuch goes on to explain that the public’s alacrity manifests itself only on special occasions. But when it comes to daily events, even, perhaps especially, the many guarantee little. It is in this type of situation that “everyone” could act, but often “nobody” does. Hence, the lechem hapanim, the 12 loaves of bread that was distributed each week to those kohanim beginning and ending their weekly shifts, had to be made of matzah only.

Presumably, this is why the korban mincha brought with the daily sacrifice also had to be made of matza[6].

Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch explains anachronistically[7] that the shtei halechem on Shavuot are made of chametz because that is the day we received the Torah. It is only with the acceptance of the Torah that we became truly free, replacing servitude to man with servitude to G-d. Thus, we are able to serve the food of free people.

[1] It is implicitly stated many times, as the Torah tells us that many of the various korbanot mincha are to be made of matza (see Vayikra, chapter 2).

[2] This is part of a much larger question touching upon the relationship between the Written and Oral Law, where the same words may be interpreted in different ways. For example, the phrase b’nei Yisrael is sometimes understood to mean all of Israel, and at times to be referring to only the males, interpreting b’nei as sons, and not as children. While there may be textual reasons for doing so, that is not always—or at least, does not always appear—to be the case. Similarly, regarding an asmachta, where the Sages connect a certain law to a Biblical verse, it is not always clear if the Sages understood their teaching to be the actual meaning of the verse or rather are just using the verse as mnemonic device to remember the law (or perhaps give it added importance), something that was crucial in the days before the Oral Torah was committed to writing.

[3] This is a fascinating and revealing comment, demonstrating the difficulty of finding meaning in all mitzvot, both for ourselves and for others. It is fine to disagree with others, but one should never attack those who are legitimately working for the sake of heaven.

[4] While it is undoubtedly a “he,” this wonderful book—to my mind, far and away the best overview (and much more) of Judaism ever written—was published anonymously (what a powerful lesson in humility) as a gift from father to son for the son’s bar-mitzvah, and to this day, its authorship is unknown. While it is often attributed to the 13th century Barcelonan rabbi, Rabbi Aharon Halevi, that view is far from conclusive.

[5] He also explains that chametz symbolizes arrogance as opposed to lowly matza, which is the symbol of humility. Arrogance has no place in the worship of G-d. While the Sefer Hachinuch does not say so, this would explain why the thanksgiving offering could be made of chametz. Ingratitude is a great precursor to arrogance, and those who are able to acknowledge that their success could not have occurred without the help of others are models of humility.

[6] With exceptions and exceptions to exceptions, one begins to see why the Sefer Hachinuch was wary of his own explanation. Furthermore, the experience and ambiance of being in the Temple is one that inspires greater meticulousness in carrying out our duties. Our rabbis even note, kohanim zerizim hem, that kohanim—regardless of what particular Temple activity they are carrying out—act with alacrity. Nonetheless, the idea that we must not delay in carrying out G-d’s will is a beautiful one.

[7] Whether we actually received the Torah on Shavuot is a matter of Talmudic debate. Regardless, such is moot, as that Torah was shattered and the Torah we have today was received on Yom Kippur. Furthermore, from the perspective of the Torah itself, there is no date set aside to celebrate the receiving of the Torah—“each day it should appear to us as new”. It was only after the destruction of the Temple and the exile of the people from their land that what was, biblically speaking, an agricultural holiday became celebrated as the day of the giving of the Torah.