The time has come for new leadership. “I am no longer able to come and go, and G-d has told me you will not cross the Jordan” (Devarim 31:2). While the people complained plenty about Moshe's leadership, clearly they were very nervous about him leaving the scene. Moshe reassured the people that all would be fine with Yehoshua, and that he, too, will have Divine assistance in his mission.

Yehoshua was also nervous. How was he to fill the shoes of Moshe Rabbeinu? Moshe reassured him that “He will be with you, He will not forsake you, and He will not abandon you; do not fear, and do not be dismayed” (Devarim 31:8). To symbolize and crystallize this continuity, Moshe presented a Sefer Torah to the Kohanim and to the elders of Israel. It is the Torah that must lead the Jewish people, and as long as our leaders are faithful to it, and expend their efforts in implementing it, we will be able to trust in G-d. It is no coincidence that the President of the United States swears allegiance to the U.S. Constitution while holding a Bible. No human being, no matter how powerful, is above the law.

Soon thereafter, we are given the last of the 613 mitzvoth: the mitzvah for each Jew to write his own Sefer Torah[1]. This placement makes perfect sense, both in the context of the change in leadership and as the concluding mitzvah of the Torah. Less clear is the mitzvah that breaks the continuity between Moshe giving a Sefer Torah to the elders and our obligation to write the same: that of hakhel,the once-in-seven-years public gathering at which the King would read parts of the Torah.

In defining when this public reading took place, the Torah tells us that it was “at the end of seven years, at the appointed time [at the conclusion of] the shmitta year, on the festival of Sukkot” (Devarim 31:10). At first glance, these three mitzvoth, shmitta, hakhel and Sukkot, have little to do with each other. During the shmitta year, the farmer allows his land to lie fallow, demonstrating his acceptance of G-d as the controller of nature (similar to the connotations of our observance of Shabbat on a weekly basis). Sukkot celebrates our journey from Egypt to the Land of Israel, and rejoicing in the blessings of the Land. And hakhel is a mass learning initiative in which men, women and children gathered together to hear words of Torah.

Yet these three mitzvoth share a most important ingredient: that of helping others. Shmitta affords the poor the opportunity to enjoy the bounty of the land, even if they themselves own none. It is not easy for a landowner to work hard—and farming is very hard work—and yet be forced to allow any and all to enjoy the fruits of his labour. Furthermore, the shmitta year cancels outstanding debts, allowing the poor a fresh start—an ancient version of bankruptcy law.

While shmitta is the sharing of our physical resources with others, hakhel is the sharing of spiritual resources with others. The requirement to bring little children, even infants, to the hakhel “ceremony” is explained by the Talmud, “so that those who bring them will be rewarded.” There is no greater reward than having our children participate in the gathering of the Jewish people, even if they are too young to understand what is happening. We toil for many years planting the seeds that will nourish others.

It is Sukkot, more than any other holiday, that demonstrates the concern one Jew must have for another. We begin by sharing the blessing of our harvest. The ushpizin, the special invitation to our founding fathers beginning with Abraham, is a message for us to emulate his chesed, loving kindness to all. “All of Israel shall dwell [together] in a sukkah”. The four species represent the various types of Jews, and if any “type” is missing or broken, the entire set is invalidated. We form a circle together in shul as we carry the lulav, in which all are equidistant to the centre. Sukkot is z’man simchateinu, the time of our happiness, a time to especially help the stranger, the orphan, and and the widow" (Devarim 16:15). In our tradition there is no greater joy than helping others.

The Torah begins with the message that man is created in the image of G-d. As Moshe—the one who actualized his G-dly image more fully than anyone else—is about to exit, he leaves us with the message that our ultimate task is to help others; materially, spiritually, enabling us to come together as a people.

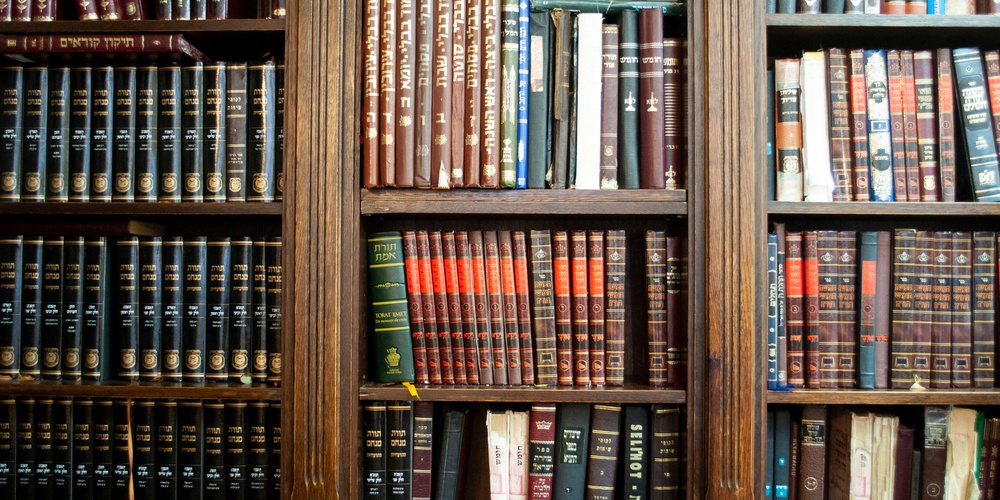

[1] Whether this obligation applies equally to women is a debate amongst later-day authorities. In practice that debate is of little relevance today as even men fulfill this mitzva not by actually writing a sefer Torah, but through acquiring Jewish books and having a Jewish library (see Shulchan Aruch, Yoreh Deah 270:2).

I would argue that with so many sifrei Torah sitting in the aron kodesh, used only on Simchat Torah, that instead of spending thousands of dollars to donate another Torah, the money be better spent in supporting Jewish education, where the need is so much greater.