“And a new king arose who did not know Yosef” (Shemot 1:6). What a difference a few years can make. In the 59 years between the death of Yosef and the birth of Moshe[1]Jews went from being welcome guests to potential enemy aliens who are to be taxed, enslaved and finally murdered. This too, sadly, can be included in the category of ma’ashe avot siman lebanim, that Biblical events foreshadow future Jewish history (see Ramban Breisheet 12:6).

Yet it would be a mistake to assume that it took a mere 59 years to go from hero to villain. It is clear that soon after the famine ended Yosef had lost much of his power. He had to beg to be allowed to bury his father in Canaan and to personally accompany the procession. With the famine over Pharaoh had little use for “A Hebrew slave youth” (Breisheet 41:12). That Pharaoh was “using” Yosef for his own purposes is apparent from day one. One wonders what it was about Yosef’s interpretation of Pharaoh’s dream that found favour in his eyes. With the good wheat and the big fat cows followed by the opposite and with food at the root of the dreams, it did not take a genius to interpret the dream.

It was not so much the interpretation as much as Yosef’s plan of action that found favour in Pharaoh’s eyes. Yosef suggested, and Pharaoh eagerly complied, that Pharaoh take control over the economy. “And let them collect all the food of these coming good years, and let them gather the grain under Pharaoh's hand, food in the cities, and keep it” (Breisheet 41:35). Concentrating power in the Pharaoh’s hands was something he was all too eager to do – as is the case with all authoritarian leaders.

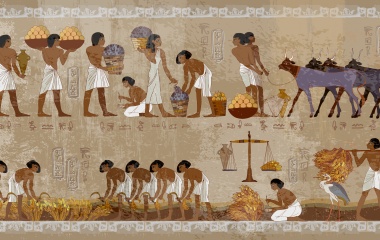

With Yosef actually implementing this new policy any anger by the people would be directed at Yosef and not Pharaoh. Having a front man to carry out one’s hurtful plans is a lesson learned well by all dictators[2]. As the famine intensified, “Joseph gathered in all the money that was to be found in the land of Egypt and in the land of Canaan, as payment for the rations that were being procured, and Joseph brought the money into Pharaoh’s palace (Breisheet 47:14). And when the people came pleading to Yosef, “Give us bread, lest we die before your very eyes; for the money is gone!” Yosef sold them the food, the same food they had grown in the first place. With no money the people were forced to sell their livestock, their cattle and eventually their land itself such that “Joseph acquired all the land of Egypt for Pharaoh” (Breisheet 47:20).

Is there any reason for an Egyptian farmer having their food confiscated and land taken not to hate Yosef? At the time, their only concern was not starving to death, but when the famine ended, and Yosef no longer Pharaoh’s right-hand man, surely there was great resentment, at the very least, towards Yosef. By the time of Moshe, Yosef’s saving of Egypt was long forgotten. The stark contrast with Yosef’s treatment of his own family was sure to arouse even more enmity. Immediately prior to telling us that “there was no bread in all the land for the famine was very severe” we are told that “Joseph sustained his father, and his brothers, and all his father’s household with bread, down to the little ones”. While the poor of one’s household come first, this is not the case when the “donor” is a political leader entrusted with public money so that they may provide for the needs of all.

In a classic case of unintended consequences, the Torah is teaching that it was Yosef himself who unknowingly lay the groundwork for the eventual enslavement of his people and the hatred that would allow the Egyptians to throw Jewish babies into the Nile[3].

Yosef was, quite understandably, focused on ensuring there be enough food so that thousands would not die during the famine. The best way, Yosef thought, was to centralize power. There was a major crisis that needed to be solved and the future took a back seat to the needs of the present. He was not thinking of where this may lead.

Considering that Yosef was a young inmate, wrongly convicted with zero political experience, coddling up to Pharaoh is perfectly understandable. But understandable as it was and notwithstanding the countless lives that Yosef saved – the most basic reason why our Sages attached the epithet Hatzadik to his name – the Torah warns us of the danger of leaders acquiring too much power. Even great tzadikim can make such a mistake. Let us learn from their mistakes and not repeat them.

____________________________________________________________

[1] According to Rabbinic tradition, from the time Yaakov arrived in Egypt until the Exodus was 210 years. The Torah explicitly states that Yosef rose to power at the age of 30 and that Yaakov arrived in the second year of the famine at the age of 130 i.e. when Yosef was 39 years old. The Torah also tells us that Yosef died at 110 and thus Yosef lived for another 71 years. With the Torah also stating that Moshe was 80 at the time of the Exodus that leaves 59 years between the death of Yosef and the birth of Moshe. If, however, we take the Torah at face value that the Jews were in Egypt for 430 years (Shemot 12:40), then the time gap enlarges significantly.

While the Sages use exegetical tools to reconcile these two traditions, that the Biblical text and rabbinic tradition would be at such variance is due to the fact that Biblical numbers (and names) are meant more as conveying varying ideas, symbols and messages.

To cite a very simple example, it is not possible that Moshe was 80 when he first approached Pharaoh, was 120 when he died and that the Jews wandered in the desert for 40 years. Such leaves no time from that first confrontation and the last of the ten plagues. While the Torah might want to use round numbers, the Torah is not averse to using non-round numbers i.e. Sarah’s death at 127 or Aharon’s at 123. Clearly the Torah was most interested in the number 40, a number with tremendous Biblical significance.

What that message is regarding the Exodus is beyond the scope of this devar Torah but for now suffice it to say that 430 links the Exodus to Avraham and 210 to Yaakov, each offering its own perspective on our sojourn in Egypt.

[2] The first time I heard the privilege to hear Rabbi Soloveitchik speak he compared the policies of Pharaoh in Egypt with those of Nazi Germany.

[3] While this may come a shock to many, classic Jewish commentaries were unsparing in pointing out the sins of our greats. Only by noting their humanity are we able to try and emulate them. The Ramban (see Breisheet 12:10 and 16:6) actually blames the sins of Avraham and Sarah for our slavery in Egypt and the persecution we suffered throughout history by the sons of Yishmael. Yosef’s actions should be classified not so much as a sin but as a mistake.