After years of tranquility in Egypt the inevitable happens and the plague of anti-Jewish decrees rears its ugly head. The accomplishments of Yosef had long been forgotten and the country was doing very well without Jewish members of government.

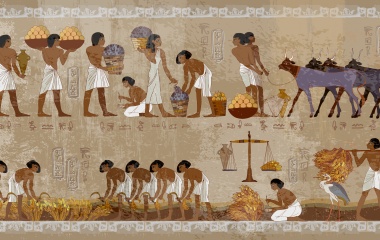

Though initially invited to come and settle in Egypt, the Jews were now seen as an unnecessary thorn in Egyptian society. The Jews, while fully partaking of the benefits of Egyptian society, stubbornly clung to their own manner of dress and speech and even refused to give their children Egyptian names. As a first step in dealing with his "Jewish problem," Pharaoh set the wheels of xenophobia in place. The census figures showed a very high Jewish birth rate which contrasted sharply with the local population growth. An immigrant quota was enforced and those immigrants who were allowed in were required to work in state run enterprises. The Torah tells us that a labour tax was imposed on the Jews who henceforth built the cities of Pitom and Ra'amses. The growing immigrant (read Jewish) presence (though they had settled in Egypt approximately 100 years earlier) brought forth accusations of dual loyalty. Perhaps if a war breaks out, the Egyptians feared, the Jews will side with the enemy instead of joining the Egyptian army. This "Egypt first" policy laid the groundwork for an attempt to exterminate the Jews. Hospital officials were told that should Jewish babies die at childbirth no investigations would be conducted. It was at this point that the stage was set for the final decree of mass murder of all Jewish babies.

The Egyptian experience with its slavery and eventual redemption was foretold to Avraham and formed a necessary pre-requisite to our becoming a nation. Why was this necessary? On its most basic level it is only when one has endured slavery that one can truly appreciate freedom. Our suffering in Egypt was meant to develop our sensitivity to others, especially the downtrodden. We who suffered so much must make sure not to inflict pain upon others. This explains the repeated prohibitions in the Torah against the oppression of strangers in our midst and the exhortations to remember the fact that we were slaves in a foreign land.

While people who suffer should be more sensitive to the pain of others, they, ironically often are the least sensitive to the plight of others. After all, it can be argued, if I went through such hard times why shouldn't others? One often hears this argument regarding benefits given to present day immigrants to Israel as compared to the harsh realities the immigrants of the 1950's faced. The Torah categorically rejects this mode of thought by emphasizing that personal suffering must lead to a desire to save others from a similar fate.

Egypt was the most advanced country of its day. Science, architecture, art and culture all flourished in Egypt. Yet these same people could degenerate into barbarians capable of killing innocent children. Law and morality, the ancient Israelites quickly learned, must be rooted in a Divine system which sees every human being as one created in G-d's image. After seeing how low man could descend, the Jews were only too eager to accept the Torah. While some may (understandably) question belief in G-d after the Holocaust, surely it is belief in man that has proven to be a false god.

Often, shared suffering can help people bond together. While hardship often brings out the negative side of people, it can bring out the best in us. The terrible tragic loss of life when terror attacks or natural disasters occur bears this out as we've seen people from around the world join together to offer help and (hopefully) prevent even greater suffering.

Perhaps the primary purpose of the Egyptian exile was to bring us together as a people, teaching us that we must help one another in times of need. By feeling the pain of others we show that the lessons of over 3,000 years ago are still relevant today.