Malcolm Gladwell, in his best-selling book Outliers, delineates how much of one's success in life is dependent on when one is born. Thus, the great innovators in computers – Bill Gates and Steve Jobs, just to name the most famous—were all born in the mid-1950s. Had they been born earlier, they would have been too old and set in their ways to switch gears when the computer revolution came along. Born later, they would have missed out on the great initial opportunities. In a fascinating chapter, he explains why the top law firms on Wall Street from the 1980s onwards were led by Jewish lawyers born around the year 1930. So much of our success is due to being in the right place at the right time.

“We learned in a braita: Rabbi Yossi [says], it would have been proper that Ezra be the one through whom the Torah be given to Israel, had Moshe not preceded him…and even though the Torah was not given by him, the script of the Torah was changed by him” (Sanhedrin 21b).

Amazing! That Moshe was the greatest prophet who ever lived is one of the 13 principles of Jewish faith as formulated by Maimonides. Yet, at the same time, Rav Yossi teaches that Ezra was as worthy as Moshe to be the one to receive the Torah. He just happened to have been born a bit too late.

The Gemara brings in textual support for this assertion. “Of Moshe it is written, ‘And Moshe went up unto God’ (Shemot 19:3) and of Ezra it is written, ‘He, Ezra, went up from Babylon’ (Ezra 7:6). As the aliyah, going up, of the former refers to the [receiving of the] Law, so does the aliyah, going up, of the latter [refer to Torah]”. While the proof text could easily be refuted[1] (though the Gemara accepts it at face value), the message behind it is most powerful.

Going from Bavel to Israel was just as historically significant as the Exodus and the receiving of the Torah. Had the Jewish people not left Egypt when they did, they would have fully assimilated into Egyptian culture and lost their Jewish identity – a fate our Sages claim did happen to the majority of the people. Moshe’s journey up to Har Sinai was the purpose of the Exodus. Similarly, had the Jewish people as a whole remained in Bavel (as most did), the Jewish people may not have survived. Intermarriage was rampant and Jewish learning no longer a priority. It would be many hundreds of years later that Rav and Shmuel would arrive from the land of Israel and bring Torah life to Babylonian Jewry, life that may have ceased had there not been a community in the land of Israel.

To verify the truth of this assertion, one just needs to think how much more assimilation there would be around the Jewish world if not for the State of Israel. For 1,900 plus years, one could likely count on one hand the number of ba’alei teshuva[2], those becoming more observant—it seemed like there was only a one-way street out of Judaism. All that changed in 1948 and especially in 1967, and today a significant amount of committed Jews are ba’alei teshuva making their own contributions to Jewish life. And equally important, many “non-observant” Jews retain strong and important ties to Judaism to a large extent because of the State of Israel.

The Gemara quotes a second proof text. Regarding Moshe, it says (Devarim 4:14), “And the Lord commanded me at that time to teach you statutes and judgments; and concerning Ezra, it is stated (Ezra 7:10): ‘For Ezra had prepared his heart to expound the law of the Lord [his God] to do it and to teach Israel statutes and judgments’”.

Moshe may have been the one who redeemed us from Egypt, but it is in his role as Moshe Rabbeinu, Moshe our teacher, by which he is forever known in Jewish lore. Had Moshe taken us out of Egypt but not given us the Torah, there would be no Jewish people. So, too, it is not enough to physically bring the Jews to Israel. One can still assimilate even in the Land of Israel.

Ezra’s importance lay not in the being the first shaliach aliyah, but in his role in saving the Torah that was literally in danger of being forgotten. He initiated a religious revolution, and it was Ezra who was a (the?) founding member of the Anshei Knesset Hagedolah. This is the body that established the basics of Jewish life that we observe today, including prayers, blessing, kiddush and havdallah (Brachot 33a), and the ones “who returned Torah to its former glory” (Yoma 69b).

The period of prophecy had come to an end, and if Judaism was to survive, it would be through the leadership of the Sages. It was Ezra who was that crucial link between the prophets and the Sages[3]. It was Ezra HaSofer, the scribe, who established the “final” text of the Torah, and it is Ezra who is the primary architect of the Oral Law.

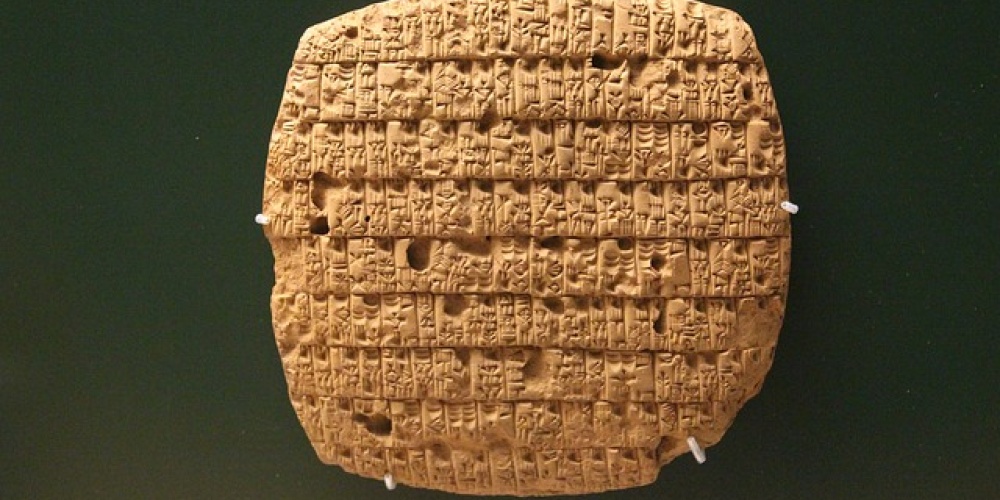

Moshe gave us the Torah, but it was Ezra who—at a crucial moment in Jewish history—ensured the survival of Torah. Had he lived earlier, he would have been the one chosen to be the eternal lawgiver. But “even though the Torah was not given by him, the script of the Torah was changed by him”. As the Gemara explains, the Torah was originally given in ketav ivri, printed letters akin to hieroglyphics and much harder to read. Ezra changed the “font” to that which we use today, known as ketav ashurit, Assyrian script, called such because it emanated from Assyria. This script is much easier to read, opening up the world of Torah knowledge to more and more people.

Whether for ideological reasons – perhaps the idea that our Torah script came from foreign sources was just too much – or because of historical belief, Rebbe Yehuda Hanassi argued that the Torah was originally given in ketav ashurit and only “when and because the Jewish people sinned, it was changed into ro’etz,[4] and when they repented, the [Assyrian characters] were re-introduced…and why was it called ashurit? Because it is me’usheret, a beautiful script” (Sanhedrin 22a) reflecting Ezra’s role in beautifying the Torah.

Each of us is born at a unique time in history. Thus, there are many positions and possibilities that are closed to us because we are just too late. There are others that are years away, and it will be other people who take advantage of those opportunities; we are just too early. But there is always much to do, whenever one may happen to live. With the world in need of so much moral clarity and leadership in so many areas, we can start by living lives of ethical integrity, demonstrating our belief that we are all created in the image of G-d.

[1] This would appear to be what in legal contexts is called an asmachta, where the text serves as a kind of hint to a teaching that one knows from other sources. In other words, the verse on its own cannot be said to the source of the teaching.

[2] Our usage of the term ba’al teshuva, referring to one who moved from a non-observant Jewish life to an observant one, is most modern. With non-observant Jews basically nonexistent for 1,900 years, there was no need for a term to describe such a phenomenon. In rabbinic literature, a ba’al teshuva is an otherwise observant Jew who had sinned and has now repented.

[3] This may explain why our Sages (Megillah 15a) identified Ezra with Malachai, the last of the prophets. Interestingly—and probably not coincidentally—the last verse of this last of the prophets speaks about the linking of the generations: “And he shall turn the heart of the fathers to the children, and the heart of the children to their fathers” (Malachai 3:24).

[4] The Jastrow Dictionary, offers no translation. Koren translates it as “impairment” and Soncino translates it only in a footnote as “to break, or dash into pieces.” In what I believe is much more than a coincidence, we do find a tanna by the name of Rav Yehuda ben Ro’etz. As far as I can tell, he has only one teaching recorded in Talmudic literature, appearing earlier in Masechet Sanhedrin: “Rebbe [Yehuda Hanassi] and Rav Yehudah ben Ro'etz, Beit Shammai, Rav Shimon and Rabbi Akiva, all hold yeish eim lemikra, that the vocalization of the text is determinant in Biblical exposition” (Sanhedrin 4a). Rabbi Yehuda ben Ro’etz teaches that it is how we read the text, not the way it is written, that is crucial in interpreting it (see here for further elaboration). That the downplaying of the written text is taught in the name of “Rabbi Yehuda ben Ro’etz” is, to my mind, striking; and I would not be surprised if there were no father by that name and that, like so many other names, “Ro’etz” is symbolic.