Shabbat and Yom Tov are gifts to the Jewish people, and the Jewish people only. As such, we are permitted to benefit from work by a non-Jew on these days--provided the non-Jew is doing such work for his own benefit (Shabbat 122b). It is for this reason that a non-Jewish contractor can do work for a Jew on Shabbat; the hours he chooses to work are his own. However, Jewish law prohibits one from asking for, or even benefiting from, work that a non-Jew does of his own accord if done specifically for the benefit of the Jew.

As this is an area where many are liable to take unwarranted liberties, Jewish law is actually stricter regarding the work of a non-Jew on Shabbat as compared to that of a fellow Jew. In the latter case, one may benefit from work done by a Jew on Shabbat--say, making (kosher) pizza--immediately after Shabbat. There is little fear that a Jew will ask a fellow Jew to perform a forbidden activity on his behalf on Shabbat. Such is not the case with a non-Jew. To deter one from asking a non-Jew to do work on one's behalf on Shabbat, our Sages ruled that one may not derive benefit from the work of a non-Jew until enough time has passed after Shabbat that the work could have been completed from beginning to end after Shabbat (Beitzah 24b). One has to wait a couple of hours before eating the pizza made by their friendly non-Jewish neighbour on their behalf.

On Yom Tov, one may engage in melachat ochel nefesh, work needed for the preparation of food for use that day: "that which is eaten by all people, that alone may be done for you" (Shemot 12:16). Our Sages needed to define the exact parameters of ochel nefesh. Thus, for example, they allowed the slaughter of animals on Yom Tov[1], but not trapping them for slaughter. That was considered too far removed from the process of food preparation.

"It once happened that a non-Jew [on Yom Tov] brought fish to Rabban Gamliel. He said, 'they are permitted, but I do not wish to receive them from him'" (Beitza 24a). As the Gemara explains, Rabban Gamliel was of the view that, in a case of doubt as to whether the animals were "trapped" before Yom Tov or only after the onset of Yom Tov, one could be lenient and allow their use. While Rabban Gamliel ruled leniently, that was for others; for himself, he presumably wanted to be strict.[2]

This is not something that should surprise us, nor was this was this an isolated phenomenon. The application of the law is as much an art as a science. As we have often noted, two people can ask the exact same question and get different answers, each appropriate for his or her own personal circumstances. So it is readily understandable that a rabbi would rule one way for others, yet act differently himself[3].

"In three cases, Rabban Gamliel was strict in accordance with the opinion of Beit Shammai...from the days of my father's house (beit abba), we would not bake large loaves, but thin wafers. They said to him, 'What shall we do about your father's home[4], who were strict on themselves and lenient for all of Israel so they could bake large loaves and thick cakes?" (Beitza 21b).

Just as there are times where it may be appropriate to adopt a more stringent position, there are times when being more lenient than others is the correct approach. "He also gave three lenient rulings...one can prepare a broiled lamb on the night of Passover. And the Sages forbid it" (ibid 22b). Rabban Gamliel was neither strict nor lenient--judging each case on its own merits.

While Rabban Gamliel ruled that one may take the fish from a non-Jew on Yom Tov, future generations debated the extent of his leniency. "Rav says: they are permitted to be received; and Levi says: they are permitted to be eaten. Rav said: A person should never absent themselves from the Beit Midrash even for a single hour, for I and Levi were both present when Rabbi [Yehuda Hanassi] taught this lesson. In the evening, he said: they are permitted to be eaten; on the [following] morning, he said: they are permitted to be received. I who was present in the Beit Midrash retracted, [but] Levi who was not present in the Academy did not retract" (Beitza 24b).

While it is most unlikely a non-Jew will bring us fish on Yom Tov, the teaching that we should spend as much time as possible in the Beit Midrash is a most relevant one.

[1] Nowadays, such is not allowed as with modern food production and refrigeration, we never eat meat the day it is slaughtered, so that there is no reason to slaughter an animal on Yom Tov itself.

[2] Rashi, apparently based on the Mishnah's wording of "he did not want to accept it from him", explains that Rabban Gamliel's refusal was specific to this non-Jew, whom he did not like--but under normal circumstances, he, too, would eat the food.

[3] Of course, circumstances might dictate that a rabbi specifically act as he rules for others. This is often the case today, where failure to do so can easily lead to cynicism.

[4] What is fascinating is that Rabban Gamliel was a direct descendant of Hillel, yet there was no hesitation for the family tradition to follow the approach of Beit Shammai.

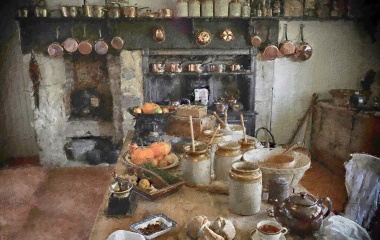

Photo by dhrubajyoti