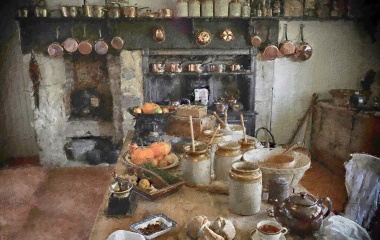

One of the manifold changes of modernity is manifest in the modern methods of food preparation. No longer must one literally spend pretty much the entire day in the kitchen in order to eat well. Speciality cookbooks – I imagine another symbol of modernity – often note the preparation time and often market themselves with such titles as “Quick and Easy” or “Short on Time”, allowing those who desire to leave the kitchen and enter the paying workplace.

In a time before fridges and freezers, combined with antiquated delivery systems food could not be prepared in advance and one’s diet consisted of very local food. What we have gained in convenience we have lost in freshness and it is the rare person who eats meat a mere hours after its slaughter or fresh pita out of the oven.

Due to this change the halacha no longer allows one to slaughter an animal on Yom Tov. As is well-known, the basic halachic difference between Shabbat and Yom Tov is that ochel nefesh, the preparation of food is allowed on Yom Tov. In Talmudic times what greater ochel nefeshcould there be than shechting an animal on Yom Tov. How else to fulfil the teaching “that there is no joy other than with meat and wine”. Even if – and that is a big if – the meat would not spoil if kept overnight–fresh meat, really fresh meat, just tastes better. But we today do not eat this way. Even if we don’t–and that is a big if –take meat out of the freezer, we are not eating it immediately after slaughter. Hence one today who slaughters an animal on Yom Tov would violate a biblical command – even if they ate the delicious meat on Yom Tov itself.

The changes in food preparation have had far reaching social, economic and educational implications[1]. At the turn of the 20th century some 60% of Canadians lived on farms, a number that is less than 2% today. With agriculture making up a much smaller part of economic output the discussion about how to properly observe the shmitta year–which begins in a mere few days–has undergone tremendous change. But one need not live in Israel, or wait seven years for the halachic impact of changes in food preparation.

As food production has moved from eating home grown produce to a multi-billion (trillion?) business and as much of what we eat is no longer 100% natural but made up of so many ingredients, keeping kosher has become a multi-billion dollar business, requiring knowledge in many areas beyond the Talmud and Shulchan Aruch. It was not long ago that one read the ingredients of a product and based on that information alone decided whether it should be eaten. What was written on the package fully described what was inside. No longer is such the case. Today those who oversee kashrut must be expert in the ways of the business world i.e. have street smarts, in addition to knowledge of the science of food preparation.

Masechet Beitza is the tractate that details the laws of Yom Tov. The Yamim Tovim of Pesach, Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Sukkot, Purim, and even Chol HaMoed each have their own masechet detailing the specifics of each Yom Tov[2]. Beitza and Chagigah are the masechetot that deal with those aspects common to every Yom Tov. Chagigah deals with the mitzvot of aliyah leregel, the mitzva to visit Jerusalem on the festivals, and those of purity and impurity, laws what we might call the chatzi lashem, the half of the day we are to dedicate to G-d. Beitza deals with the laws of eating on Yom Tov, what we might call the chatzi lachem, the half of the day for our own personal enjoyment. With one possible exception each of the 42 Mishnayot deals with the topic of food.

The opening Mishna (Beitza 2a) famously begins with a debate between Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai as to whether one may eat an egg that was laid on Yom Tov.

If one needs any indication of changed eating habits here it is. Had we today been editing the masechet surely we would have begun with the second chapter and the laws of eiruv tavshilin, something that is needed on a regular basis, at times three times within four weeks. We would likely place the third chapter dealing with catching fish on Yom Tov, the fourth chapter discussing the laws of transporting wine and even the fifth and final chapter which discusses bringing fruit laid out to dry into the house when it rains, before discussing a chicken laying an egg on Yom Tov. All, I imagine, are for most people more common occurrences than dealing with a newly laid egg on Yom tov something I have never encountered. But for those living in the time of the Mishna, an egg laid on Yom tov was a most regular occurrence. Whether one could eat such an egg was a most relevant question – and one that takes up six pages of Talmudic discussion.

In trying to understand the reasoning for the view of Beit Hillel that the egg is forbidden, Rabba postulates that we are dealing with a case when Yom Tov is on a Sunday. Since “any egg that was born today was finished yesterday” (Beitza 2b) and yesterday was Shabbat this would be a “violation” of the principle that we cannot prepare on Shabbat for Yom Tov. If so, Abaye[3] asks, why does our Mishna not make such a distinction, thereby implying that regardless of the day of the week the egg is prohibited. The Gemara answers that in theory such an egg should be permitted. However, the rabbis were concerned that if eggs born on the other days of the week were permitted one might mistakenly (or not) eat an egg laid on Sunday. While this may be a bit far-fetched for us urbanites, it is not hard to imagine the need for such a rabbinic decree.

Yet, if so the Gemara wonders, why did the Braitta teach that if one slaughters an animal on Yom Tov– something that surely happened thousands of times every Yom Tov–and finds an egg inside the chicken one may eat the egg. Why not make a decree forbidding such lest one accidentally eat an egg that was laid on Yom tov. To this the Gemara answers that finding an edible egg in a slaughtered chicken is a rare occurrence and one does not make decrees for rare occurrences. There is little doubt that for the farmers of old it was much more likely to encounter a ready to eat egg in the slaughtered insides of a chicken than for city dwellers of today to encounter an egg born on Yom Tov.

While our methods may have changed, that food plays a major role in our celebration of Yom Tov has not.

[1] It is fascinating that at least one remnant of agricultural society refuses to allow for changes. The long summer vacation for students has its origins in the need for ‘all hands on the farm’ during the summer. Despite the changed circumstances the summer break continues.

[2] Shavuot has too few laws to warrant its own masechet. Furthermore, it is seen as an extension of Pesach, much like Shimnii Atzeret is the extension if Sukkot. Hence the Mishnaic name for Shavuot is Atzeret.

[3] Abaye asked this question not to his colleague and bar-plugta, interlocutor Rava, but to his teacher, Rabba.