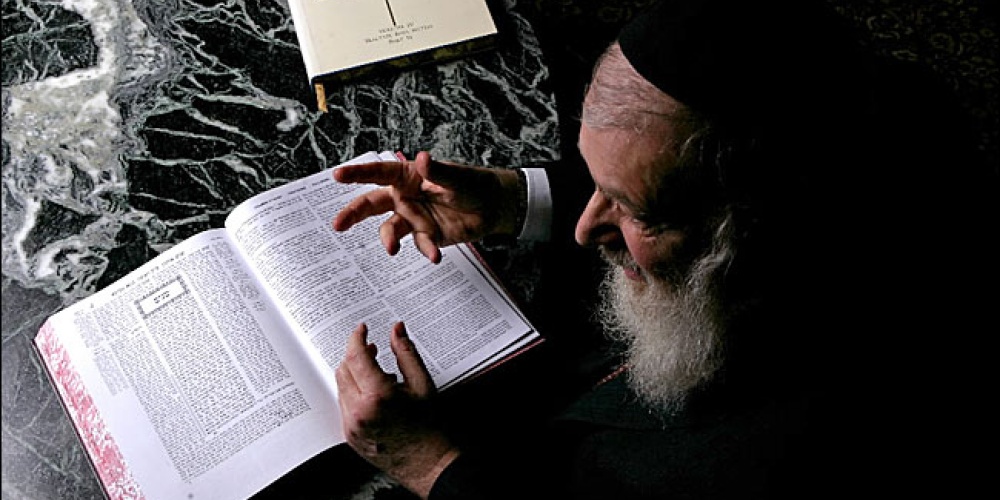

Great literature lends itself to multiple, even contradictory, interpretations. And the Bible is--in addition to everything else--great literature. "Isi ben Yehuda said that five verses in the Torah ein lo hechreh, have no definitive reading: shet (lifted up), mesukadim (shaped like almond blossoms), machar (tomorrow), arrur (cursed), v'kam (stand up)" (Yoma 52a-b). Isi ben Yehuda refers to five biblical verses in which a word can be read with what comes before or with what follows.

Moshe tells Joshua to "go and fight Amalek...I will stand on the top of hill with the rod of G-d in my hand" (Shemot 17:9). Where I have put ellipsis appears the word machar, tomorrow. It is unclear whether machar should be read with the first half of the verse, as in go fight Amalek tomorrow; or with the second half, so that that the verse reads that they should fight Amalek today, but only tomorrow will Moshe go to the mountain.

Similarly, it is generally understood that Yaakov, on his deathbed, cursed Shimon and Levi for their killings of the people of Shechem in retaliation for the rape of Dinah. Such an interpretation assumes that the word arrur, cursed, by which Yaakov "blesses" Shimon and Levi introduces the words that follow, apam ki az, so that the verse reads "cursed be their anger, [which] is fierce". However, Isi ben Yehuda raises the possibility that arrur is the concluding word of the immediately prior phrase[1] referring to the people of Shechem, so that it is they who are cursed, with Yaakov noting (praising?) the fierce anger of Shimon and Levi. Which of these is the correct interpretation? Ein lo hechreh, there is no way to determine; nor does it matter. Or to put it differently, both are true[2].

If the Torah is written in such a way as to have two (or more) possible readings, that is because both have their place. Maseh avot siman lebanim, the actions of our forefathers are a sign for us. What Yaakov actually did is much less important than which we can learn from Yaakov's actions. And depending on the given situation, there is a time to take revenge against our enemies and a time when it would be ill advised (and hence a terrible sin). Sometimes we must fight today, and sometimes it's best to wait another day.

Our Sages teach that each day we must perceive that the Torah is being given anew (see Rashi Devarim 26:16). And thus, each day we must carefully weigh the best response to any given situation.

While the teaching above is quoted in the name of Isi ben Yehuda, the Gemara tells us that he actually had five other names by which he was called, not including his real name, Isi ben Akiva. I find it most interesting that a teaching about "lack of clarity" would be taught by someone whose name is a bit unclear.

Isi ben Yehuda appears infrequently in the Talmud. One of his teaching is the inclusion of non-Jews in the obligation "to stand before the elderly". Isi ben Yehuda greatly valued life experiences, with the lessons learned making all the elderly worthy of special honour. While there seems to be little connection between these two teachings of Isi ben Yehuda (and there may not be one) perhaps there is. As one gains life experience and matures, one realizes that many things in life ein lo hechreh, have no definitive answer. And it is those same life experiences that help greatly in learning how to apply life's lessons to any given situation.

[1] Prima facie, this reading seems implausible, as the word arrur is the first word of the verse; so it is difficult to claim that it refers to the prior verse rather than the verse where it actually appears. Presumably, Isi ben Yehuda is reading an actual Torah scroll, where there are no verses (Ritva) or questioning whether the way we break up the verses is the correct one (Maharsha).

[2] The other three biblical words listed that we cannot determine how to read refer to the placement of the almond-like design on the menorah (Shemot 25:34), G-d's response to Cain's anger for having his sacrifice rejected (Breisheet 4:7), and Moshe's exhortation to the people of Israel to follow the ways of the Torah after he dies (Devarim 31:16).

photo by Vincent Laforet, New York Times