Rosh Hashanah conjures up images of prayer, repentance, and new beginnings. It is the time of year when we are more focused on spiritual matters and our own mortality. Yet Masechet Rosh Hashanah opens by listing the four New Years our tradition observes. Not only is Rosh Hashanah not the only New Year, the first of Tishrei is only one of the four days on which the world is judged—the others being Pesach (wheat), Shavuot (fruit), and Sukkot (water). Much of Masechet Rosh Hashanah details the laws of kiddush hachodesh, the sanctification of the new moon. Only in the second half of the masechet do we deal with the themes of "our" Rosh Hashanah—shofar and the special tefillot of the day.

If Rosh Hashanah marks the beginning of the year, kiddush hachodesh marks the beginning of Jewish national history. It was the first mitzvah given to the Jewish people and with it, the process of redemption began.

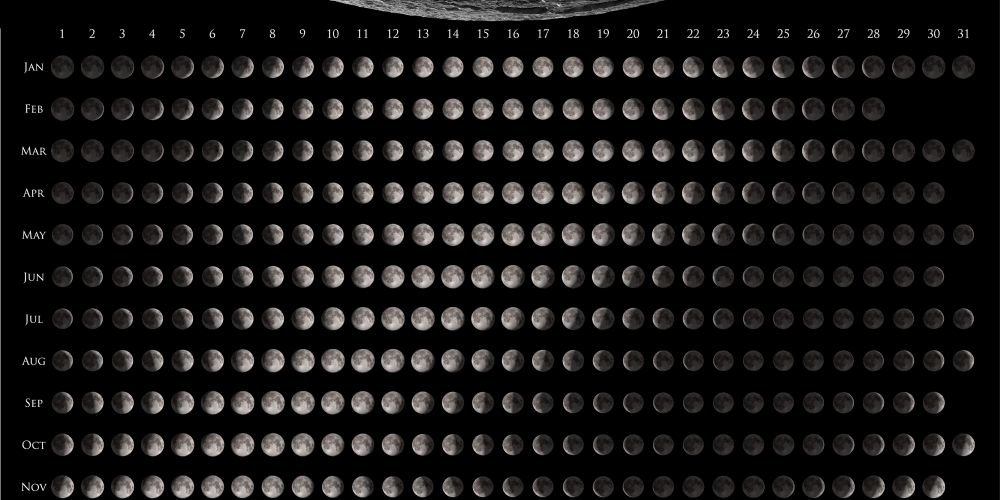

Our calendar is meant to be a fluid one, with the declaration of the new month to be determined by the testimony of witnesses. If two witnesses testified to the sight of the new moon on the 30th day of the previous month, that day would then become day 1 of the next month, and the previous month would have only 29 days. If witnesses did not come, then day 31 would automatically become day 1 of the next month.

The Mishnah discusses in great detail many fascinating details of this mitzvah. One of the more interesting laws of kiddush hachodesh was that witnesses were allowed to travel on Shabbat in order to testify that they saw the new moon. Rabbi Akiva "held back more than 40 pairs of witnesses at Lod"—after all, only one pair is needed, so why allow extra desecration of Shabbat? However, "Rabban Gamliel sent [word] to him: 'If you hold back the masses, you will find that you will fail them for the future'" (Rosh Hashana 21b). They will not bother to travel in future months when their testimony might actually be needed. Thus, all who travelled to Jerusalem were given the courtesy of being allowed to testify before the court—even though their testimony was not actually needed.

While witnesses could travel on Shabbat, the messengers sent to inform those in the Diaspora of the correct date for the declaration of the new month could not. This need for messengers was a result of the sectarian battles besetting Rabbinic Judaism during the second Temple period. The "minim", sectarians, and the "kutim", Samaritans, tried to manipulate the calendar so that the holiday of Shavuot would fall on a Sunday. This would be in keeping with the simple, but incorrect, reading of the text that the seven-week omer count was to begin on a Sunday. Originally, fires would be lit on each of five mountains moving north from Jerusalem, and from there to the Diaspora—in the days before electricity, fire on a mountain could be seen for many, many miles. The sectarians, however, started lighting their own fires, so that a new method of communication was needed. Hence, the sending of messengers, who might spend weeks travelling through the Diaspora; and hence, the origin of the second day of Yom Tov. Not knowing if the previous month was 29 or 30 days, they would observe a second day.

Of course, even amongst those committed to the Oral Law, there was fierce disagreement over the calendar. The Mishnah records a dispute as to whether we should accept the testimony of witnesses who claimed they saw the moon on the night of the 30th day, yet no moon was seen on the 31st night. While Rabban Gamliel, the head of the Sanhedrin, accepted their testimony, Rabbi Yehoshua did not—"How can we testify that a women gave birth and on the next day, her belly is between her teeth? (ibid 25a)".[1]

As in his dispute with Rabbi Akiva, Rabban Gamliel took a long-term view and insisted that Rabbi Yehoshua violate the day he had calculated to be Yom Kippur. While his handling of the issue was harsh, without strong action the Jewish people would have split into two. I have often noted that, despite all the denominational battles in the Jewish world, at least we all agree when Pesach is. I shudder to imagine what the Jewish world would be like if our arguments included the dating of Yom Kippur.

The second half of the masechet discusses the mitzvah of shofar and the special davening on Rosh Hashanah, both of which have had many stages of development from Talmudic times to today.

The discussion of kiddush hachodesh in the context of Rosh Hashanah reflects the combination of human and Divine. Rosh Hashanah acknowledges the eternal unchanging G-d as the Master of the Universe. Kiddush hachodesh is carried out by temporal, fickle man. Yet in distinction to all other areas of Jewish law, even if the court is factually wrong in declaring the new moon, they are "right"; and their (mis)calculation must be followed. Our Sages go so far as to teach that G-d does not sit in judgment of the world until the Jewish people declare the month of Tishrei.

Man was created on Rosh Hashanah to be G-d's partner. We accept the Kingship of G-d in all we do, but G-d "depends" on us to complete His creation and to let Him know when we shall be judged.

[1] Of course, this is not a fool-proof argument as often, after birth, a woman can still look very pregnant.