Judaism has long recognized that we need both private and public space. Man is both an individual and a member of a community. At times, the individual must conform to communal norms, but more often than not, it is the community that must respect the rights of the individual.

That these spaces must remain separate is given legal form in the biblical prohibition of transferring objects from a public to a private domain (and vice versa). While this halachah need be observed only on Shabbat, the message must resonate all week. In addition to these two biblically recognized spaces, the rabbis added two more, known as a carmelit and a makom p'tur; what we might translate as a hybrid area--say, a side street--and a no-man's land. Because a carmelit has the features of both a public and private domain, it is forbidden to carry to or from a public and private domain to a carmelit. On the other hand, one may carry to and from a makom p'tur to any domain; being a no-man's land, it is open for all purposes.

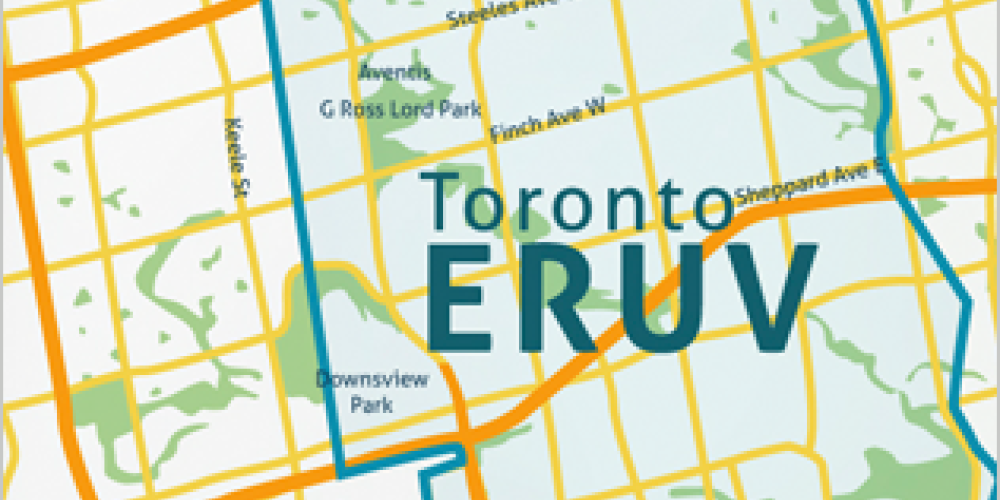

Masechet Eruvin is about breaking down barriers. There are times when one desires to let another into his private space. Therefore, the halachah devised a mechanism by which one could, through the use of an eiruv, join otherwise separate areas into one. (There are times when this is impossible, but those cases are rare). Known as aneiruv chatzerot, the joining together of courtyards, it requires that we physically enclose the area with a wall, wires, fences, or the like. In addition, each household must contribute--or have contributed on their behalf--some food that is held in a common location, uniting all inhabitants around this one location.

The word eiruv means to mix and join together, and our tradition has two additional eiruvin. An eiruv tavshilin joins the distinctive days of Yom Tov and Shabbat, allowing one to cook on Yom Yov for Shabbat; an eiruv techumimallows one to walk beyond the city limits, joining together two geographical areas.

What unites all three eiruvin is food. One begins the cooking process for Shabbat prior to Yom Tov, allowing one to continue to cook on Yom Tov itself for Shabbat. Normally, one may only walk 2,000 cubits (roughly equivalent to a kilometre) outside of city limits. While for most people today this is a non-issue, this was quite germane when many lived in towns consisting of a few hundred people--or even now, when one finds oneself at a summer cottage. By placing some food outside of the city limits, one is able to walk an additional 2,000 cubits outside of the city.

It is food that creates a bond between people, establishes a person's residence, and signifies that preparations for Shabbat have begun.

Interestingly, by scrambling the letters of the word eiruv, one gets ra'av, hunger. We must join together, both on a private and a public level, to ensure that no one goes to bed hungry.