"And these are the names of the sons of Israel who came to Egypt". The above verse serves as the opening to the second book of the Torah, setting the background to Jewish life in Egypt. One would also be correct in stating that the above verse is taken from parshat Vayigash, listing those who came to Egypt. In other words, the opening of verse of Shemot appears most redundant, adding no new information to the story of the Jewish people.

Rather, its repetition highlights the changing environment the Jewish people would soon find themselves in. Sefer Breisheet goes into great details of the life, triumphs and travails of Jacob and his family. No detail is too insignificant in this emotional and riveting saga.

Yet in Sefer Shemot, the children of Jacob are no more than the heads of families who, with no warning and in the blink of an eye, find themselves as slaves. It is the same people, but oh, how different was their actual arrival in Egypt from how their arrival is perceived years later!

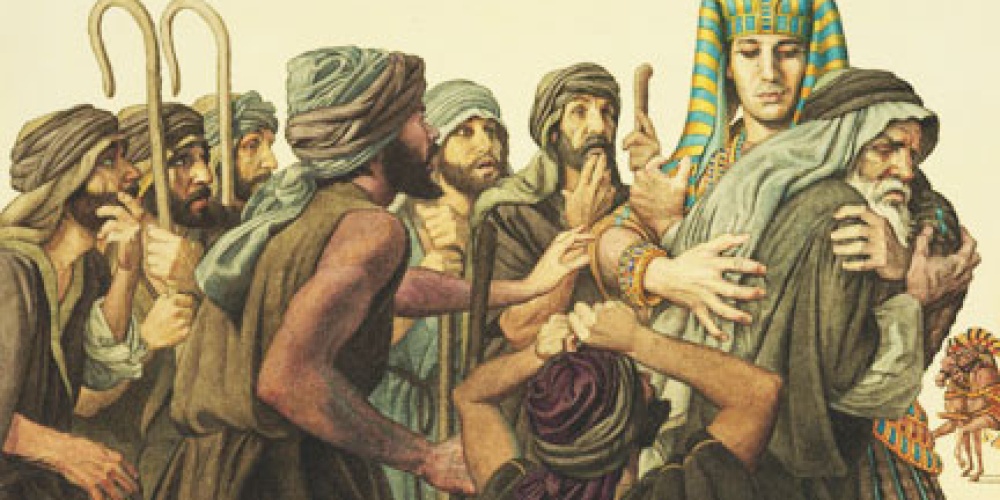

Invited by Pharaoh to "bring your father and your family and come to me and I will give you the best of the land of Egypt" (Breisheet 45:18), they are long forgotten by a "new King who knew not Yosef" (Shemot 1:8). They are no longer families, but a dehumanized mob who "we must deal wisely with", by imposing taxes, labour and ultimately, death upon them. From Yosef to Moshe we meet not even one single Jew. The contrast between the children of Israel of Sefer Breisheet and those same children years later is a most painful one.

"A man from the house of Levi went and took the daughter of Levi" (2:1). The last we heard of Levi he, along with his brother Shimon, was being cursed by Jacob for his "weapons of violence" used to kill the people of Shechem. They arose to avenge the rape of their sister and years later, it was the sister of the son from the house of Levi who would save her brother, allowing the redemption to occur. And true to Levi's legacy, the first action the Torah ascribes to Moshe is the killing of an Egyptian who was beating "a Hebrew from his brothers" (2:11). As Shimon and Levi killed to avenge their sister, Moshe did the same to rescue his "brother".

It is feeling the pain of his brother, pain that he--living in the Royal Palace--did not share, that set Moshe on the path to leadership. Yet while his killing of the Egyptian may have been justified[1], such a person is unfit for leadership, and Moshe had to be exiled before he could assume leadership. And when, years later, he witnesses the terrible sinning of his people, he leaves it others to inflict punishment, the tribe of Levi (not surprisingly) with the idolatry of the Golden Calf and Pinchas with the sexual immorality at Shitim (see Bamidbar 25:1-9).

During his many years in Midian, Moshe learned to channel that burning desire for justice represented by the tribe of Levi to the most noble of causes. And with Aaron--to whom the pursuit of peace was so natural--and Miriam at his side, the Jewish people were ready to be redeemed.

But it was not only the actions of Levi that Moshe had to "refine" and redirect. It was Yosef who most unwittingly laid the groundwork for the enslavement of the Jewish people. And this goes beyond the sale of Joseph as the catalyst for the Jewish people coming to Egypt. It was Yosef as "Minister of Agriculture" (he wore many hats) who centralized political authority and economic control in the hands of Pharaoh. From there, it was a short step to the enslavement of not only the Jewish people, but effectively all of Egypt[2]. It would take ten plagues and then some to set the people free. At the moment of the Exodus, when Moshe takes the bones of Yosef with him, he is removing more than his body.

The sons of Jacob who arrived in Egypt with such fanfare would leave with much the same many years later, ready for their march to redemption. Shabbat Shalom!

[1] It is interesting to note that as Levi was criticized by his father for his actions, there are voices within our tradition that criticize Moshe for his killing the Egyptian. See the studies of Nehama Leibowitz z"l (Shemot, 4), where she quotes Midrashim that ascribe Moshe's not being allowed to enter the land of Israel to his killing the Egyptian.

[2] I owe this insight to Leon Kass and his masterful book Genesis: The Beginning of Wisdom.