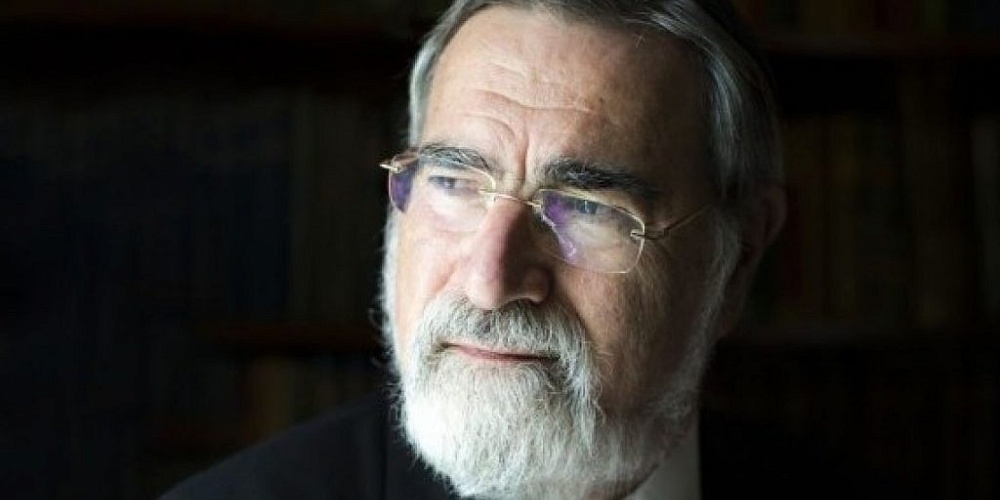

I had the honour of sharing a few words in honour of Rabbi Sacks zt"l at the moving program Mizrachi of Canada organized this week. I share my words below.

I am honoured and unworthy to be asked to say a few words in memory of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks zt”l.

What made Rabbi Sacks so special? Why did so many people look to him for inspiration?

I believe it begins with his educational choices. Rabbi Sacks was a student of philosophy. He focused on the grand ideas and ideals of Judaism, never losing sight of the big picture. Like Saadia Gaon, the Rambam, Gersonides and Rav Soloveitchik before him, he mastered the philosophical teachings of the day. Moreover, he knew how to translate those ideas into the cultural language of our times, enabling him to speak to the issues of the day.

Just last month his latest book, Morality: Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times, was published. It is morality that sums up his life. Rabbi Sacks was the moral beacon we so badly needed, trying to heal the broken and divided world in which we live. With his powerful voice of reason, a voice of hope, a voice of responsibility, he sought to bring people together and bring healing to the world.

Rabbi Sacks took seriously the teaching of our Sages, Who is wise? Halomed mikol adam, one who learns from all people. He understood that we can learn from all people and from all religions. We at Torah in Motion had the honour of hosting Rabbi Sacks for our tenth anniversary celebrations. We had a program at University of Toronto, where he engaged in conversation with the Roman Catholic philosopher Charles Taylor (an event we dubbed Lord and Taylor). He began his remarks by saying how excited he was to be there. He noted that Jewish tradition teaches that upon seeing a non-Jewish scholar, one must make a bracha, and proceeded to make the bracha with shem umalchut, invoking G-d’s name as he recited the bracha, shenatan mechachmato lebasar vedam.

Because he was lomed mikol adam, he could be melamed l’kol adam, teach all people. There were few who reached more people, and none who reached a wider spectrum. He reached well beyond the Orthodox world that he inhabited, inspiring and influencing Jews of all persuasions; perhaps more important, he reached out to and impacted upon the non-Jewish world. This is, unfortunately, something all too rare today. He was the moral voice of the UK and as in the days of old, the influence of this British “royal” reached the four corners of the globe. He was an or lagoyim, sanctifying the name of G-d far and wide. He made us proud to be Jews.

Rabbi Sacks was a master orator and a master writer. While the great ones in all fields make it look easy, becoming a master takes hard work, followed by more hard work. His poetic use of language and range of sources, the verbal portraits he would paint, and the relevance of his message were a joy to behold. He had the ability to take the mundane and make it special. He could take ideas that we have known since kindergarten and shine a new light on them, allowing the old to be renewed. I can think of no better introduction to tefillah than his introduction to the Koren siddur. His introductions to the various machzorim are nothing short of masterpieces, resonating with meaning to the novice and learned alike.

Jonathan Sacks had intended to become Dr. Sacks, professor of philosophy. As a young student at Cambridge, he came to New York to see—amongst others—the Lubavitcher Rebbe, who turned the meeting on its head, asking him what he was planning to do for the Jewish people. It was that meeting that changed the course of his life, leading him to become the Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, author, teacher, orator, friend of royalty, leader, all the while serving as the ambassador of the Jewish people.

I believe this is the idea that informed his understanding of the rasha of the Pesach seder. Ma ha’avodah hazot lachem, what is this service to you? (s)he asks. Commentaries throughout the ages have struggled to explain what makes this child a rasha. Rabbi Sacks, in what he himself called a “radical re-interpretation”, explains that the child turns to his parents and asks them, Ma haavodah hazot lachem, what does Judaism mean to you? You want me to be a proud Jew, to take my Judaism seriously. What type of model, Mommy and Daddy, have you displayed? If we want our children to take their own Judaism seriously, we have to model that life for them. Only if we love Judaism, ve’ahavata et Hashem, can we properly veshinnantem lebanecha, teach our children.

The Rebbe was asking the young Jonathan Sacks, Ma havodah hazot lecha? What are you going to do to bring the beauty of Torah to others? Rabbi Sacks took that message to heart, understanding that he now had a great mission, one that transformed his life and the lives of thousands, perhaps millions, of others.

I think the best way to honour the memory of Rabbi Sacks is to ask ourselves, Ma havodah hazot lachem? What does Judaism truly mean to us? What are we doing to ensure the beautiful message of the Torah is central to our lives? What are we doing to make a difference in our own lives, and in the lives of those with whom we come in contact? Yehi zichro baruch.