Perhaps no Biblical story fascinates us like that of Yosef and his brothers. Its twists and turns are full of drama, intrigue, tragedy, violence, sex, cunning and pathos, and features common folk and royalty alike. It even has a happy ending—everything to ensure a best seller.

The Torah’s interest lies not in the excitement of the story, but in the multifold lessons derived from its proper analysis. The Torah is well aware that couching the crucial lessons of life in a story is much more effective than a list of instructions. Those instructions—known as mitzvot—can only be effective after the stories of Breisheet have been learned and relearned.

We meet Yosef as a 17-year-old, somewhat immature teenager. He is wont to snitch on his brothers and has no compulsions about sharing his egotistical dreams with all, arousing both hatred and jealousy.

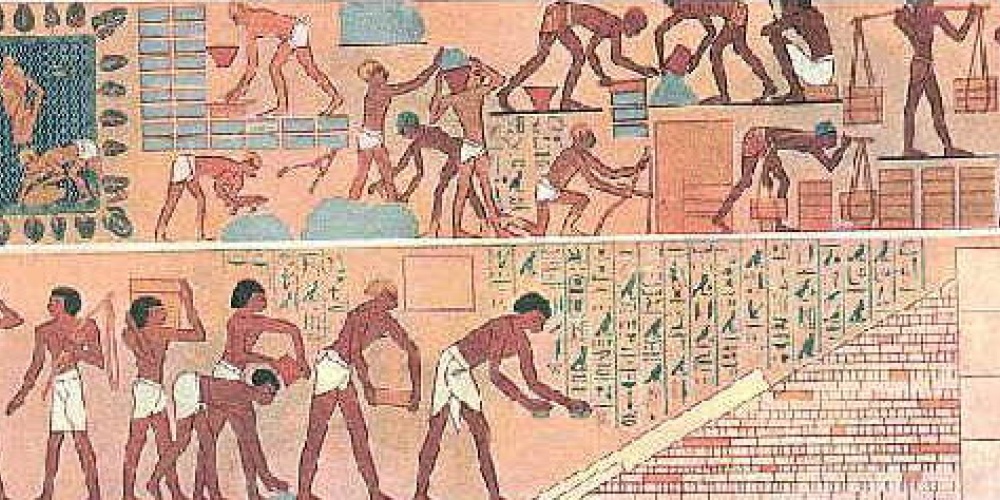

It took Joseph many years to mature and develop into Yosef Hatzadik, the appellation our Sages grant him. One would think that after his narrow escape from death in the pit, he would learn the danger of arrogance. Yet often those who survive crises and turmoil do not necessarily become better people. It is no surprise that the Torah exhorts us no fewer than 36 times to be kind to strangers, because “you were strangers in the land of Egypt” (Bava Metzia 59b). Despite knowing the horrors of slavery, there was a real fear that once masters in their own country, the Jews would succumb and enslave others. Often those who suffer the most become the cruelest. If they had to endure pain, so must others. They may even interpret their later success as due to the experience of suffering, which allows them to justify to themselves bringing hardship unto others. It does not. Oh, how people neglect to learn from their past.

Joseph was no different. Rising to prominence in Potiphar’s house, Joseph seems to consciously try to forget his past. Our psychological makeup is such that we blot out unpleasant memories. Yosef makes no attempt to contact his father to let him know he is alive and well. His only goal appears to be setting up a new life in his adopted homeland. He is, as the Torah itself testifies, successful, and is soon appointed master of Potiphar’s estate.

Interestingly, it is at this point that we are told, “Yosef was of beautiful form and fair to look upon” (Breisheet 39:6). Surely this statement should have been made when Joseph was first introduced to us, as is the norm in the Torah. Our Sages thus understood this phrase not as a physical description of Yosef, but rather a moral one. Yosef was most interested in the latest fashions and making sure his hairstyle was contemporary. His crying, aging father was the furthest thing from his mind. Considering what his family had done to him, this was perhaps understandable, but G-d expected much more from the beloved son of Yaakov. Immediately thereafter, we read how “his master’s wife cast her eyes on Joseph: Sleep with me, she said” (39:7).

Joseph wavered, unsure whether to take that final last step into Jewish oblivion. What saved him, our Sages claim, was the image of his righteous father that appeared before him. When push came to shove, the intensive Jewish upbringing that Joseph had protected him from falling prey to the degenerate effects of this most modern of cultures. It was his past that laid the foundation for the future.

Today, we live in a culture no less threatening than that of ancient Egypt. Many succumb, and many make unnecessary compromises. To gain from our encounter with the modern world, we must make sure that the images ingrained in us are those of uncompromising commitment to Jewish values and morality. These images must be strong enough to form our core essence, enabling us to draw upon them when our values are challenged by those around us.