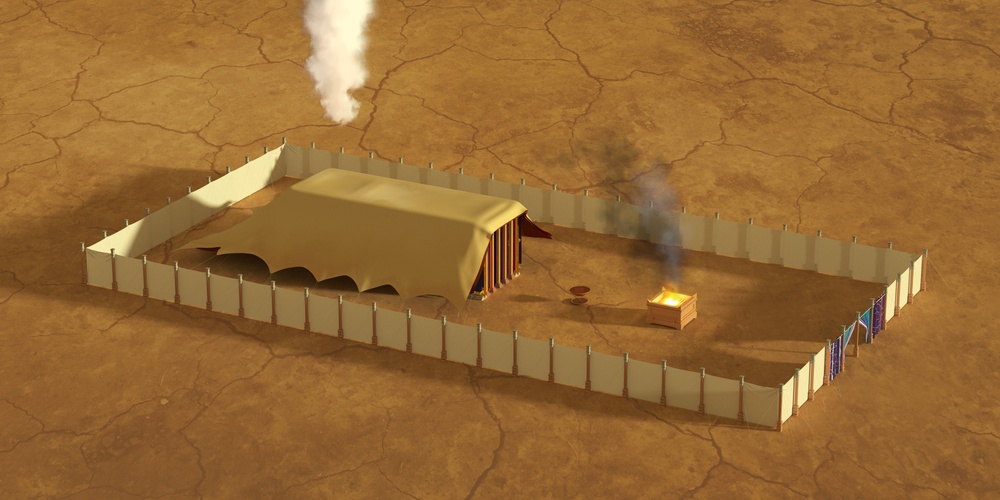

Just as the Shabbat is the pinnacle of physical creation, the Mishkan is the pinnacle of spiritual creation. The Exodus and the revelation at Sinai find their ultimate expression in the Mishkan, which completes the redemptive process. It is for this reason, the Ramban explains, that the command to build the Mishkan is included in sefer Shemot. While Shabbat serves to remind us that G-d is the ultimate Creator, the Mishkan symbolizes G-d's continuing presence amongst us.

"They shall make for Me a sanctuary and I will dwell among them" (Shemot 25:8). The physical world of Breisheet and spiritual world of matan Torah merge together in the construction of the Mishkan, inextricably linked to the celebration of Shabbat. The central aspect of Shabbat, the definition of the 39 melachot, is derived from those activities necessary for the building of the Mishkan. It is interesting that, while man must cease his creative activities on Shabbat, the operation the Mishkan continued uninterrupted and virtually unchanged on Shabbat. Man’s efforts to build, even something as vital as the Mishkan, must be halted; but G-d's presence must be felt each and every day, especially on Shabbat.

The central focus of the Mishkan was the aron, the ark that housed the luchot habrit, marking the covenantal relationship between G-d and the Jewish people. The ark was cast in gold, with golden rings on each corner to hold the "two carrying poles of acacia wood so that the ark can be carried with them" (Shemot 22:13-14). These poles were not only a means of transportation, but a permanent fixture of the ark. "The poles must remain in the ark's rings and not be removed" (v.15). While similar rings and poles were also placed on the shulchan (the table) and the menorah, those poles were to be removed once the tabernacle was in place. Why this distinction between the ark and the other vessels of the mishkan?

Rav Shimshon Raphael Hirsch, the 19th-century exponent of an engaged orthodoxy, explains that the ark's portability is a metaphor for the essence of Torah. Torah is neither rooted in nor connected to any one place or time period. Its applicability transcends any historical circumstances. The poles affixed to the ark, ready for transport, in a symbolic reflection of this idea. Jewish law was not developed as a means of survival in the exile, only to be discarded upon our return to our ancestral homeland. Nor, despite its many laws relating to the land of Israel and to national institutions, is the Torah meant to be applied only when the people of Israel are living in the land of Israel. Torah may emanate from Zion, but its message spreads to wherever Jews, and even non-Jews, reside.

The Jewish people have lived in all corners of the world and under all types of social, political, and economic frameworks, often surviving with little other than their spiritual heritage. The ability to apply the Torah in a meaningful way to whatever surroundings we encountered was, and is, the key to Jewish survival. Torah and life, halacha and real world issues, were never seen as enemies but rather as partners in infusing life with a divine purpose. Torah can and must be able to respond coherently, honestly, and meaningfully to all that life can muster.

At times our surroundings were so hostile that we retreated—sometimes voluntarily, sometimes by force—into self-contained ghettos, unable to fully apply the dynamic nature of Torah. In the modern world we all inhabit today, we must make sure that our divine Torah speaks to the issues confronting society. Whatever the topic—be it advances in medical technology, corporate ethical issues, the tendency towards religious extremes and fundamentalism, environmental issues, democracy, egalitarianism, or gay rights--those who value Torah must intelligently confront these issues.

With the center of religious life returned to Israel, our ability to apply Torah in a modern world is absolutely crucial. Although the ark, the physical vessel for the Torah, is portable, the shulchan and the menorah are firmly connected to the land of Israel. Rav Hirsch explains that the shulchan, which held bread, represents the material life and success of the Jewish people. The menorah, a vessel of light, represents the spiritual and intellectual achievements of the Jewish people. While we have had some degree of success in these matters during our years in exile, it is only when the Jewish people dwell in the land of Israel that we can develop a thriving economy based on Torah values. Only as a nation dwelling in our own land can our spiritual and intellectual genius be made fully manifest. The laws of the Torah can be observed anywhere, but the fullness of Jewish life can only be achieved in Israel.

Thank G-d, today, when our people are returning to our land, we have much greater opportunities to reflect the Divine presence in the complete Torah life. May we soon merit lighting the menorah, eating from the shulchan, and placing the aron in the holy of holies.