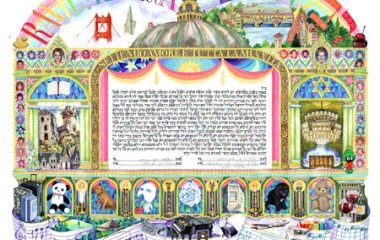

The Ketuba is one of the best known, but least understood, documents in Judaism. Read at every wedding, many mistakenly believe it is a marriage document not realizing that it is the first prenuptial agreement instituted for protection of the wife. It guaranteed the woman a fixed amount in the event of divorce or death of the husband. Recall that until the ban of excommunication by Rabbeinu Geshom in the 10th century a man could divorce his wife against her will, leaving her empty handed on the street. Hence the need for financial protection.

The Ketuba was to be paid before other claims on the estate of the husband and before the estate was divided amongst surviving heirs. The reading of this most unromantic document at every wedding was instituted only in the Middle Ages as a way to "waste some time".

Initially the two parts of the wedding ceremony were conducted up to a year apart. The Kiddushin, today universally done by the giving of a ring from husband to wife, marked the first step. While a Get was required to break this union the couple, remained in the respective homes of their parents until the Nissuin, the actual marriage, held under a Chuppah followed by Yichud (the couple spending time alone). During this break the couple prepared for their life together - primarily by ensuring the husband had a job and they had a place to live. Oh how times have changed! Whereas in Talmudic times couples would marry without living together today many live together without getting married.

Such a system could potentially work when marriage took place at a much younger age, yet it carried the risk that if the woman would be intimate with another man she would be guilty of adultery. The disputes that arise when the husband discovers his wife is not a virgin serve as the opening theme of masechet Ketubot. The claims and counter claims of how this may have happened and its monetary ramifications take up much of the first two chapters of the masechet.

Soon after the Talmudic period this waiting period was done away with in favour of the system we have today where the Kiddushin and Nissuin take place just minutes apart. Yet such creates a halachic issue - even if most minor when compared to avoiding potential adultery.

Both the Kiddushin and Nissuin are recited over a cup of wine - each with its own boreh pri hagefen. Yet if we are drinking these two cups of wine back to back we should really only make one bracha. However doing so would mean that we would make one bracha on two mitzvoth as opposed to having a separate bracha for each mitzva. By separating these two parts, by having a hesech hada'at, letting our mind wander, then the second cup would require its own bracha. Hence we took a break by reading of the Ketuba - preferably in a slow deliberate manner. It is for this reason that Rav Schachter recommends that the rabbis speech under the Chuppah take place at this point allowing for a greater separation of the two cups of wine[1].

Today the Ketuba serves more as a beautiful tradition than an actual legal document. It is rarely used as a legal document and when divorce arises the courts - rabbinic and secular - generally make their rulings, with the full agreement of the couple, irrespective of what the Keutba may say. Many grooms have little understanding of what exactly they are obligating themselves to[2]. And as one learns masechet ketubot one comes to the realization that many of the clauses, which if missing the Gemara says would invalidate a Ketuba, are nowhere to be found in our Ketubot[3].

Even more fundamentally the nature of society today is such that we rarely need fear a man would too readily give a divorce. Today we face the opposite problem; that of men refusing to give their wife a get, turning them into agunot. We owe a great debt to Rabbi Mordechai Willig who was the driving force behind the halachic prenup, a modern day Ketuba if you like, which has effectively solved the agunah problem for those who take advantage of it[4].

The Gemara rules that one may not remain married (live together) for even one minute without a Ketuba. The Rama (Even HaEzer 66:3) ruled that with the ban of Rabbeinu Gershom such is no longer true -as the ban serves as protection for the woman making the Ketuba less critical. We are not yet at the stage where it is forbidden to marry without a pre-nup. While it may not be forbidden it surely is foolhardy[5].

[1] Of the many honours given out a wedding, reading the Ketuba i.e. wasting time with reading a technical document, is perhaps the least important. It is a much greater kavod to recite one of the sheva brachot, or give a meaningful derasaha. The fact that many view the reading of the Ketuba as such a great honour reflects the inability of many to read and understand ancient Aramaic.

[2] I recall Rabbi Haskel Lookstein (who reads the Ketuba most beautifully) in a session he gave in our practical rabbinics course instructing us that while we should explain all parts of the wedding ceremony in English to those assembled we should never translate the Ketuba. Explain briefly (and selectively) what it is but no translations - people might be shocked. Of course this should not preclude the chatanand kallah from understanding their rights and obligations under the Ketuba.

[3] When I asked Rabbi Avishai David, who read the Ketuba at our wedding, about this his response was exactly that - the Ketuba today is more of a tradition than a legal document.

[4] While there are hundreds of agunot desperately awaiting a Get, to the best of my knowledge and the people at ORA (The Organization for the Resolution of Agunot), not one of them involves someone who signed a prenup.

[5] Perhaps we can compare it to the teshuvot of Rav Moshe Feisntein (Igrot Moshe, Choshen Mishpat 2:76) who ruled that while smoking is foolhardy it could not technically be forbidden. One could apply to them the principle of "G-d guards the fools". As the dangers of smoking became more and more well-known (and as fewer and fewer took up smoking) the Rabbinical Council of America (representing hundreds of rabbis and including many first class poskim) formally forbade smoking according to Torah law.