Great poetry resonates across generations and even cultures, with all finding different layers of meaning that speak to them. Yet at the same time, many great poets with the ability to speak on many levels are writing about themselves, reflecting their personal triumphs and tribulations, which in turn reflect the highs and lows of so many others.

“Our Rabbis taught the songs and praises that David Hamelech said in the Book of Psalms; Rabbi Elazar says he spoke them in reference to himself, Rabbi Yehoshua said he spoke them in reference to the community, and our Sages say that some are said in reference to the community, and some are said in reference to himself” (Pesachim 117a).

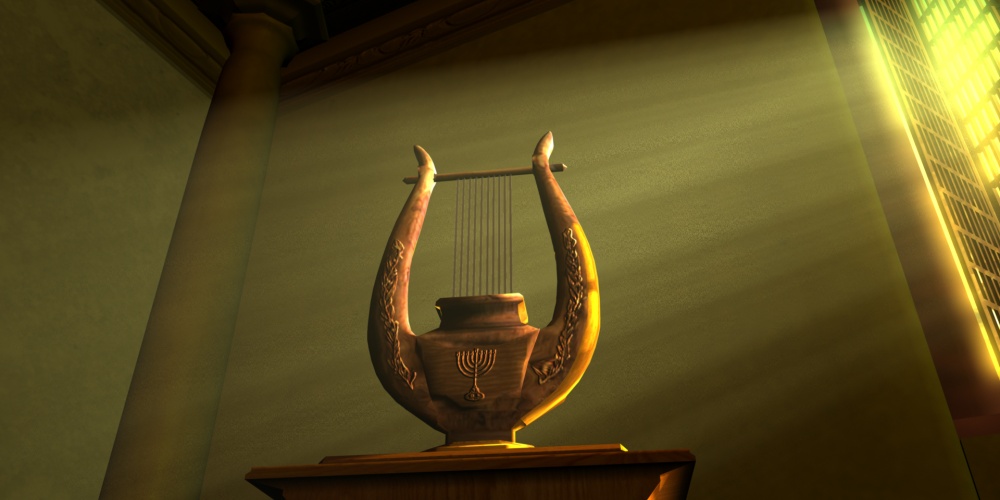

There is no figure in Tanach who experienced the ups and downs of life like our eternal king, David. And there are few, if any, who had such wide–ranging “careers” and interests. Singer, king, warrior, romantic, visionary, communal leader, legal expert, singer, dreamer, friend, enemy, builder, musician—there is little he did not experience. Small wonder he is the eternal poet of the Jewish people, whose words fill our prayer book, help celebrate our holidays, comfort the bereaved, beg for healing, and serve as the opening words at pretty much any Jewish function. Centuries before daf yomi, many a pious Jew has faithfully recited the daily chapters of Tehillim, completing the 150 chapters every month. In the beautiful words contained therein, we find hope and despair, joy and sadness, fear and confidence, reality and idealism, described with such beauty, passion and feeling.

Many of the psalms contain an introductory phrase (i.e., lamenazeach, for the conductor) that sets the tone for the mood of the psalm. Order of words is very important, and whether a psalm begins ledavid mizmor, for David a song, or mizmor ledavid, a song for David, is significant. The former, the Gemara suggests, indicates that first the divine presence rested on David, and then he composed the song; whereas mizmor ledavid “teaches that he first composed the song, and afterwards the Divine presence rested upon him; teaching that the Divine presence does not rest on man neither in laziness, nor melancholy, nor in frivolity, and not in lightheadedness, and not when engaged in meaningless pursuits, but rather, from the joy of a mitzvah (simcha shel mitzva)”.

The Divine presence is everywhere, but not all can feel its comforting hands resting upon them. It takes hard, serious work to feel the Divine presence. The lazy, or frivolous, or even the sad cannot feel the presence of G-d. But those who exude joy—who, like G-d, see good all around them—can merit the Divine presence. “And you shall rejoice before G-d”. When one is before G-d, when one can feel the awesome presence of greatness, there will be great rejoicing. While there are many earthly pleasures—and G-d wants us to enjoy them—they cannot compare to the joy of the presence of the Divine. But that presence can only be felt if we exude joy ourselves.

Sadly, many—even those who submit to them—see the demands of Judaism as a burden. Those who are fortunate to see them as necessary hard work, enabling us to reach closer to the Divine, will merit great joy as they reach higher and higher.