Many people, upon receiving notice of jury duty, try hard to avoid actually doing such. They have little time, interest, and often cannot afford the heavy financial price a long trial may entail--not to mention that often jurors are sequestered, cut off from contact with the broader world. If such is the discomfort for the judges, how much more unpleasant is it for the litigants themselves? I imagine there are few who desire to be involved in a court case--and generally, it is only when people feel they have no other method to get what is rightfully theirs do they turn to the courts.

It is this avoidance of the courts that helps explain a Mishnaic ruling regarding the rights of a widow.

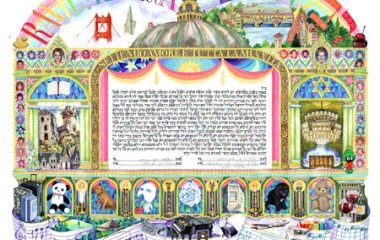

Our Sages ordained that a couple may not live together absent a Ketuba. This original pre-nuptial agreement was designed to protect the wife from financial abuse and offered financial security in the case of divorce or death of the husband. Our Sages insisted that the obligation to pay the value of the Ketuba took force upon Eirusin, the first stage of the marriage process, even though Nissuin, the second stage of marriage in which the couple actually begin living together as husband and wife, would take place up to a year later. Thus, even if the couple actually never lived together, the wife[1] could collect her Ketuba if her husband passed away (or they divorced).

How such a woman actually goes about collecting her Ketuba is the source of Mishnaic dispute. "A widow, whether from Eirusin or from Nissuin, can sell [her late husband's estate to satisfy the Ketuba] without the sanction of the court. Rabbi Shimon says, from Nissuin she may sell without the sanction of the court, from Eirusin she may sell only with the permission of the court" (Ketubot 97a).

Besides cohabitation, the primary difference between Eirusin and Nissuin is that the husband is obligated to provide support for his wife only after Nissuin. Rabbi Shimon argues that if there is no obligation for support, there is no reason to allow the wife to sell her husband's estate without a court order to do so. With no immediate need for the funds, we can afford to wait for a court-administered sale.

The Gemara presents two reasons as to why the Sages disagree. Ulla presents a rather startling argument that such a policy will increase the love a woman would feel towards a man, so that "the women not hold back from marrying the men" (Rashi 97b, s.v. meshoom cheinah). It is hard to imagine a woman preferring to remain single over the concern that she may have to go to court to get her Ketuba if her "husband" should die before the wedding. Yet those who have been involved in the shidduch world know that all too often, people, for the flimsiest of reasons, decide not to pursue a relationship--expecting another, better one will come along. Ulla is afraid that if a potential match is rejected, another one may not come so fast, or even at all. And while people are loathe to admit it, monetary concerns play a crucial role in one's choice of a marriage partner. Anything done to allay the fears of the woman in this area is to be pursued.

Rav Yochanan argues that allowing the women to sell off the estate without a court order was instituted "because a person does not want his wife to suffer the indignity of having to go to court". The courtroom is a harsh place. "When the litigants stand before you, they should be in your eyes as wicked" (Avot 1:8). People lie, cheat, and distort, and those in the courtroom must be viewed in such a light. Mercy has no place in a courtroom, where justice and justice alone must rule, and where what would otherwise be lashon hara becomes obligatory. It is not a pleasant place to be[2], and it is for this reason that a woman may sell her husband's estate in order to collect her Ketuba without the consent of the court--despite the fact that there is no immediate need to do such.

The practical difference between these two approaches regards one who is divorced. Though there was once great love between this ex-couple, no longer can we assume the ex-spouse cares whether his ex will suffer the indignity of appearing before the courts. Sadly, love can turn to hate and hate can lead to spite. It is for this reason the ketuba was needed in the first place, and this is the reason no one should be allowed to marry without a modern day halachic pre-nuptial agreement.

[1] It is most difficult to translate the status of Eirusin into our terminology. It is a legal marriage, one requiring a get to dissolve, but with husband and wife remaining in their parents' home until the Nissuin, the use of the term husband and wife--while technically true--seems a bit odd. The term "betrothal" does not capture this status, as they are legally married. What is sadly clear is that in today's world, where many couples live together before marriage, finding a term for a status of married but not living together will take some creativity.

[2] It could very well be that this is the reason the Torah exempts women from the obligation to testify in cases of criminal and, at times, monetary law. A cursory look at the Mishnatiot of the 4th chapter of Sanhedrin aptly demonstrates why one would want to avoid testifying in such cases.