"Take Aaron, and Elazar his son, and bring them up to Mount Hor; and strip Aaron of his vestments, and dress Elazar his son in them; Aaron shall be gathered in and die there" (Bamidbar 20:25-26). It was only after Adam and Eve sinned in the Garden of Eden that man had a need for clothing: "then the eyes of both of them [Adam and Eve] were opened and they realized that they were naked" (Breisheet 3:7). Up until the point of sin, the spiritual and physical worlds were in complete harmony; there was no need to cover any parts of our physical being. After sin was introduced, the physical and spiritual worlds were thrown into tension, necessitating that we cover much of our physical bodies. "And they sewed together a fig leaf and made themselves aprons". Clothes are the symbol of sin.

With the sinning of man, death became the fate that awaits all flesh and blood. When we return our souls to G-d, we can no longer cover up our blemishes, we are stripped of all our material. Death renders our clothes unnecessary, and Jewish law thus ordains that upon the death of a relative, we tear our clothes.

The death of Aaron was to be marked by the removal of his clothes, yet Aaron died only after meriting the sight of his son Elazar being dressed in his clothes. Having suffered the death of two of his sons, Aaron could go to his own death comforted in the knowledge that his son would succeed him, something denied to Moshe himself. This made the dressing of Elazar a fitting tribute to Aaron, but a most difficult task for Moshe. The Torah, sensitive to such internal feelings, specifically notes that Moshe faithfully carried out the command of G-d. "Moshe stripped Aaron's garments from him and dressed Elazar his son in them".

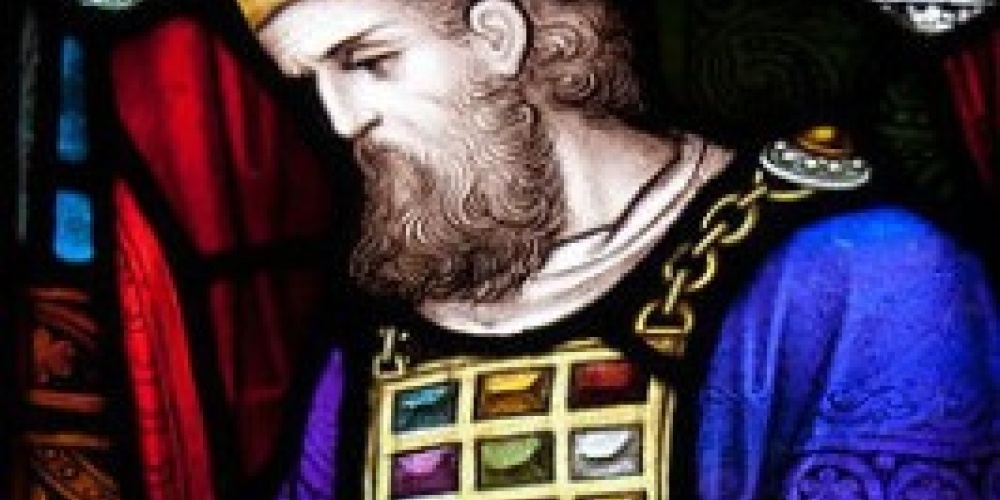

While clothing may originate in sin, clothing can also be used to elevate man. Priests working in the Temple would be required to wear special clothing "for honour and glory", and the sight of the high priest dressed in all his regalia would serve to inspire us to serve G-d.

This is not the first time that Moshe helped Aaron with his clothing. "He [Moshe] placed the tunic upon him [Aaron], and girded him with a sash, he dressed him in the robe and placed the ephod upon him" (Vayikra 8:8). The Torah describes how, item by item, Moshe dressed Aaron in his special vestments.

Here, too, dressing Aaron was no easy task. As Moshe was about to consecrate Aaron as the high priest, he hesitated. Like many a great leader, delegation was not something that came easily to Moshe. He would handle all major tasks himself, or so he thought. Even though Yitro had already warned him of the folly of such a choice, it was not easy for Moshe to give up the priesthood. The Torah alludes to this by placing the liturgical note of shalshelet, a long and winding note that goes up and down, reflecting the hesitation involved. Interestingly, a note appears on the side of this verse noting that the verse describing Moshe dressing his brother is the middle verse of the Bible, indicating that somehow this verse encapsulates the central theme of the Torah.

The ability to faithfully—without a whimper of protest—carry out the will of G-d, even when deep inside it hurts, is the true mark of greatness. This is doubly difficult when you see others get what you feel should be yours. It was this ability that distinguished Moshe from his first cousin Korach, who was unable to hold back his disappointment at being passed over for a political position.

How we dress, both ourselves and others, says much about who we are. Do we use clothes to try and cover up our faults, by masquerading as others? Or do we view our clothes as a mechanism by which we try to bridge the material and spiritual worlds? The answer to that question will help determine whether we will be able to pass, figuratively and perhaps literally, our clothes on to our children.