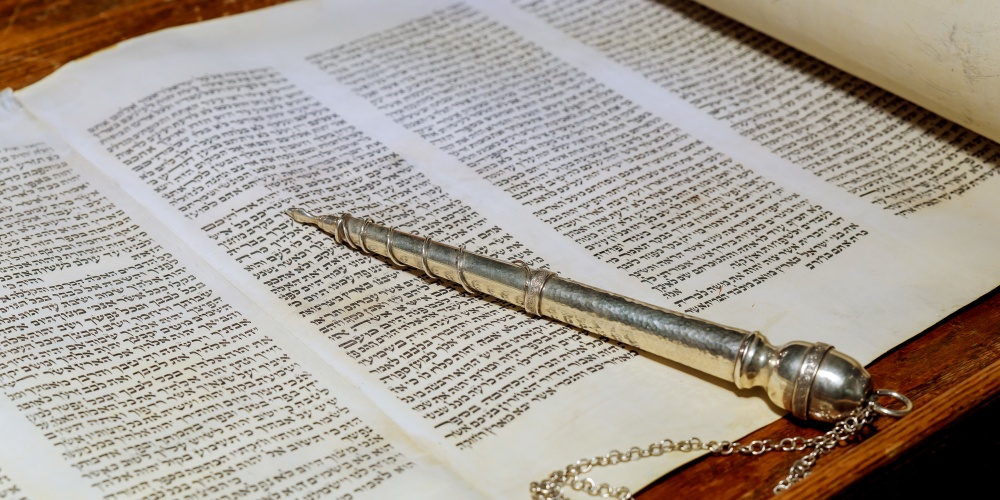

A mark of a good book is a clear and coherent structure. The opening chapters set the tone, themes are appropriately developed, and the conclusion ties together the key elements of the story. Thus, when studying the Torah, we must look for instruction not only from its content, but also its form. What is the relationship between law and narrative? Why are certain laws introduced when they are? Why is the chronological sequence not always followed? What is the significance of the many seeming repetitions? These are just some of the many questions asked about the Torah's "editorial policy". Rashi's opening comment on the Torah is not a question of understanding text, but structure, enquiring as to the purpose of beginning the Torah with the story of creation as opposed to the first mitzvot given to the Jewish people.

A quick perusal of Sefer Vayikra points to the crucial importance of structure. While Sefer Vayikra is known as Torat hakohanim, the law of the priests, it contains much more than that. Rather than a series of laws pertaining to the Temple, it weaves together ritual and ethics, interpersonal demands and those relating to our Creator, laws pertaining to society and those guiding the individual. The Torah forcefully rejects the compartmentalization of life into secular and holy spheres. All of life is imbued with holiness, and defining a person's religiosity by ritual alone misses the richness of the Torah's expectations for man and society. Priestly service and a Temple have no meaning if they are not supported by social and economic justice.

It is in this vein that we must ask why the Torah chooses to end Sefer Vayikra with a list of the rewards for observing the Torah and, even more prominently, a list of the dire consequences of disobeying its rules and regulations. Why not place these warnings immediately after the covenant at Sinai, or perhaps at the end of the Torah itself? Why at the end of the middle section of the Torah?

While Sefer Vayikra is the third of the five books of the Torah, that is the case only because of the wayward ways of the Jewish people. Had the Jewish people not sinned in the desert, there would have been no need for much of Sefer Bamidbar. And Moshe would not have had to spend the last weeks of his life preparing a new generation to enter the land of Israel, thus obviating the need for much of the book of Devarim. In other words, Vayikra should have marked the end of Torah law, and a much-shortened Bamidbar would have recorded the triumphant entry of the Jewish people into the land of Israel. Viewing the Torah from this perspective, the emphasis on reward and punishment is most logical. After receiving the law at Sinai, building a mishkan, and readying ourselves to enter the land of Israel, we are reminded that all this is contingent on our obedience to the word and will of G-d.

Yet the tochecha does not quite mark the end of Vayikra. The Torah follows these harsh words of rebuke with a strange set of laws dealing with the "worth" of man, detailing the monetary amount that one must give to the Temple if one wants to dedicate "one's value" to G-d.

The Torah begins with the story of creation. This is meant not so much to highlight the role of G-d as Creator as to emphasize that man is created in the image of G-d, and must partner with G-d in the ongoing process of creation. Man, who is here for a fleeting moment on a planet that is no more than a tiny speck in the vast universe, is nonetheless a reflection of—and partner with—the Divine. The Torah begins and Vayikra ends with the description of the importance of man. We begin with G-d endowing man with his Divine image, and "end" with man literally dedicating himself to Divine service.

Sadly, the inability of the Jewish people to live up to their potential caused death and despair. Tragically, the Torah actually ends with the death of Moshe Rabbeinu, which like all deaths marks the loss of our Divine image and removes our ability to perform mitzvot. May we utilize the time allotted to us to actualize our full potential.