Language plays a crucial role in national identity. Those of us living in Canada know how sensitive issues of language can be. Theodore Herzl devoted his life to the Zionist movement, yet—as hard as it is for us to imagine—he envisioned German as the language of the Jewish state.

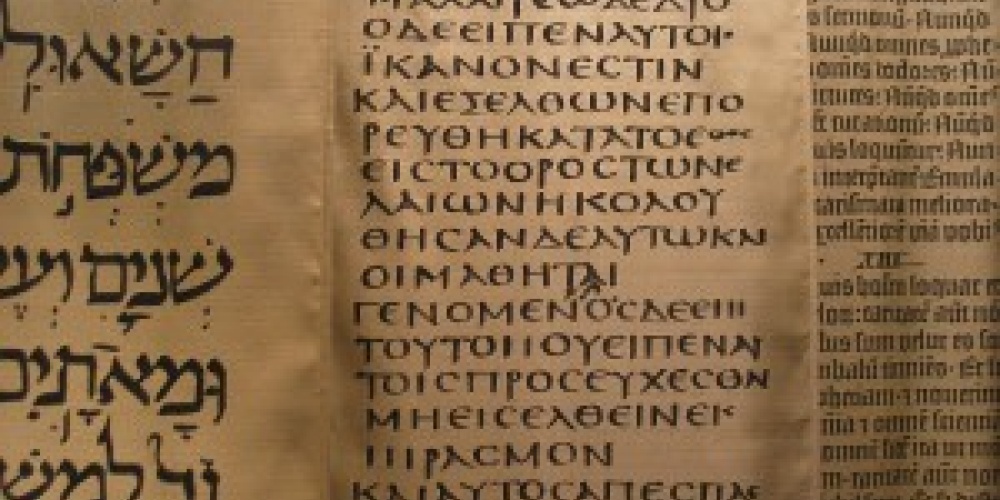

“For these three events I instituted a fast: The Greek King forced me to write (translate) the Torah to Greek”. So begins the selichot of Asara B’Tevet. No translation, no matter how accurate, can fully capture the meanings of the text in translation. And the richer the text, the more you lose. If there are 70 faces to the Torah, 69 of them are lost in translation.

The Shulchan Aruch (Orach Chaim 580) writes, “on the eighth of Tevet, the Torah was written (translated) into Greek, in the days of Talmi the King, and darkness descended to the world for three days”. When we think of three days of darkness, we are reminded that “there was a thick darkness throughout the land of Egypt for three days” (Shemot 12:22). The link between Torah in the vernacular and the plagues of Egypt is most understandable, in light of the rabbinic teaching that we were redeemed from Egypt because we did not change our language. The Jewish people may have abandoned the teachings of the patriarchs and matriarchs, even ignoring brit milah, but their retention of Hebrew as a spoken language prevented their total assimilation, allowing them to soon receive the Torah.

Translating the Torah into Greek was apparently a historical disaster for the Jewish people – one worthy of a fast day (or even three fast days). A people that cannot understand its own classic texts in the original is a people doomed to oblivion.

Yet things are not quite so simple. “On the other side of the Jordan, in the land of Moav, Moshe began to explain the Torah saying”. As Rashi notes, Moshe explained the Torah in 70 languages, one for each of the “70 nations” of the world. Explaining the Torah properly means speaking in a language (both literally and figuratively) that people understand. If we did not teach Torah in English, or promote Torah study in other languages, fewer people would be able to study it. The increase in Torah learning due, for example, to the Schottenstein (and now Koren) Talmud, with their English translations and commentary, is astounding. There are literally hundreds of thousands of hours, perhaps millions, spent on Torah study every day that otherwise would not be so spent, just because Torah is available in English. If Torah were available only in Hebrew, millions would have no access to it. No wonder the fast of the 8th of Tevet is ignored nowadays.

It seems that we have a conflict between what is in the best interest of individual Jews, and what is in the best interest of Judaism as whole. As long as Jews do not speak Hebrew fluently, they will need access to Torah in other languages. Yet the fact that Jews do not speak fluent Hebrew is tragic and a threat to their future survival.

It is only in the State of Israel that one can resolve this problem. No matter how far many of the founding fathers of Zionism were from leading a religious life, they understood that our link to our land made it mandatory that Hebrew be the language of Israel.

Asara b’Tevet, along with Tzom Gedaliah, the 17th of Tammuz, and Tisha b’Av commemorate, in one form or another, the exile of the Jewish people from the land.

As the Rambam (Laws of Prayer 1:4) notes, with exile the Jewish people soon lost their fluency in Hebrew (“They did not recognize to speak the [language of the] Jews”) and were unable to properly express themselves in their native language. This loss of fluency forced the sages to introduce a fixed text for prayer, i.e., the Shmoneh Esrei, transforming prayer from worship of the heart (“asking for the needs we need”) to a common fixed text. No wonder prayer is so difficult for us.

“In ten utterances was the world created” – and those divine utterances were in Hebrew. If exile is associated with loss of Hebrew, the resurrection of Hebrew as a spoken language is, we hope, a sign of redemption, leading to our fast days being transformed to days of joy and gladness.