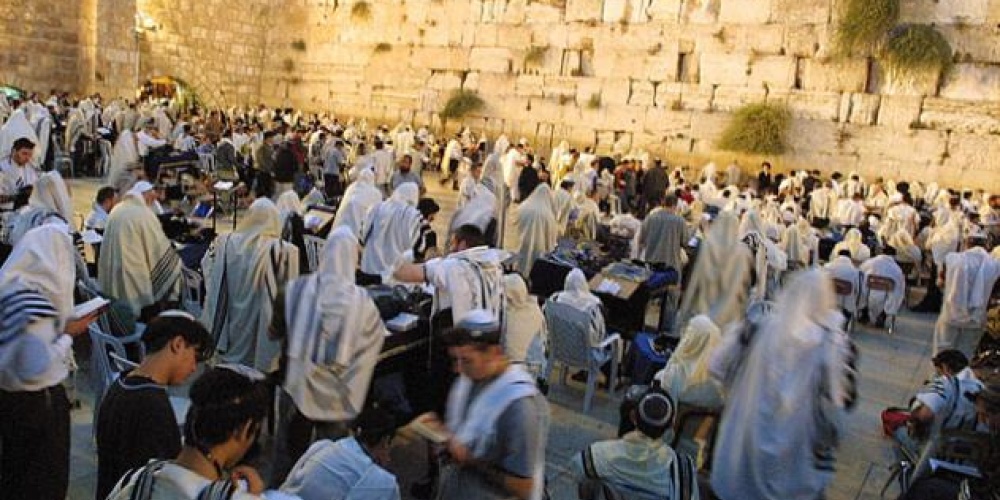

"Rav Yochanan said: Were it not written in the text, it would be impossible for us to say such a thing; this verse teaches us that the Holy One drew His talit round Him like a shaliach tzibbur, communal messenger, and showed Moshe the order of prayer. He said to him: Whenever Israel sins, let them carry out this service before Me, and I will forgive them" (Rosh Hashanah 17b). It is based on this passage that the recital of G-d’s thirteen attributes of mercy are the focal point of our prayers whenever we beseech G-d to forgive us[1]. They are the focus of the Selichot prayers, and are the focus of the davening on Yom Kippur itself[2].

The thirteen middot are so powerful that Rav Yehuda declares, “A covenant has been made with the thirteen attributes that they will not be turned away empty-handed”. What is left unexplained is why this might be so.

It is hard to believe that the mere recital of words, no matter how special, can actually bring forgiveness. Over and over, our prophets railed against mere expressions of remorse--even (especially?) the act of bringing sacrifices--if not accompanied by action. The haftara chosen by our Sages for the morning of Yom Kippur reads, “Is such the fast that I have chosen? The day for a man to afflict his soul? Is it to bow down his head as a bulrush, and to spread sackcloth and ashes under him? Will you call this a fast, and an acceptable day to the Lord? Is not this the fast that I have chosen? To loose the fetters of wickedness, to undo the bands of the yoke, and to let the oppressed go free, and to break every yoke? Is it not to feed bread to the hungry, and to bring the poor into your house? When you see the naked, and you cover him and do not hide from his flesh" (Yishayahu 58:5-7).

It is not saying the thirteen middot that gains one atonement; it is doing them that guarantees G-d will hear our prayers[3]. “What is the meaning of the text: You shall walk after the Lord your God?…Rather, copy the attributes of G-d. Just as He clothes the naked, you, too, should clothe the naked. The Holy One, blessed be He, visited the sick; you, too, should visit the sick. The Holy One, blessed be He, comforted mourners; you, too, shall comfort mourners. The Holy One, blessed be He, buried the dead; you, too, should bury the dead” (Sotah 14a).

We, who are created in G-d’s image--who were created to complete G-d’s incomplete creation--can do so by following in the ways of G-d. How can one not forgive one who acts in such a way?

Yet it appears that we are to strive even higher. Not only are we to act like G-d, but we are to (kveyachol) be like G-d. “'And I will adorn Him'[4]: Abba Saul interpreted [this to mean], 'and I will be like Him; just as He is gracious and compassionate, so you shall be gracious and compassionate'" (Shabbat 133b).

One can often act in ways that do not reflect his or her true self. This is our claim to teshuva: that while we may sin, we are not, at our core, sinners. We have given in to temptation, but we are good people--we really are. Will one act compassionately without being fully compassionate? While the Gemara in Sotah has great praise for acting in a compassionate way, the Gemara in Shabbat wants us to be compassionate people.

“And it was evening and it was morning, day one”. The Midrash, troubled by the use of the word echad, one, as opposed to rishon, first, comments that yom echad refers to the one, the most special day of the year. Yom Kippur is the most beautiful day. “There were no days of joy for the Jewish people as Yom Kippur…”. It is the day of forgiveness, atonement, and reconciliation. It is the day to ignore our human needs and limitations as we soar to the heavens, joining with the angels in offering praise to G-d[5]. It is the day our Divine image is most manifest. And most importantly, it is the day that must inspire us on all the other days of the year.

[1] It is on days of judgment that we most need G-d’s forgiveness. While Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are the days of judgment for mankind, Pesach, Shavuot, and Sukkot are also days of judgment (for grain, fruit, and water) and hence, the thirteen middot are recited on those days.

[2] While most of our Machzorim only have us reciting the thirteen middot at Maariv and Neilah, Rabbi Soloveitchik was insistent that they be said during each of the five prayer services of Yom Kippur. In those minyanim that follow his rulings, special piyutim are added in Shacharit, Mussaf, and Mincha, followed by the thirteen middot.

[3] The expression used by Rav Yochanan is “yashu k'seder hazeh, they should do this order". Saying is not enough.

[4] The teaching is much stronger in the Hebrew vanvehu, which can be read as ani vehu, me and Him, or "I am like Him".

[5] This is the basis of the custom to sing “the song of honour” with its deep praise of G-d on Yom Kippur night; and this explains why many were opposed to such songs on any other day of the year.