Often, when studying Gemara, we fail to appreciate how different day-to-day life was for our ancestors. Yeshiva study tends to focus on conceptual analysis of the legal sections of the Talmud. Even in the academic world—where there is an appreciation for the importance of “realia”, understanding the daily life patterns[1]—much of the focus is on studying the development of the text, analyzing manuscripts, and the like. Yet analysis of day-to-day life is often vital to a full understanding of the text[2].

During Talmudic times and well beyond, the idea of having a daily shower was unimaginable for all but the very wealthy. Showering was a luxury—perhaps akin to going to the spa for us—and was treated as such. Yet parallel to this, the use of a mikvah—at least during Temple times[3]—was much more widespread and common than today. The laws of purity and impurity, so forgotten today, but so central to life in ancient Israel, necessitated such.

It was not unrealistic to assume that people might combine these two activities—using the mikvah as a kind of shower[4]. “If [Yom Tov] falls on the day after Shabbat, Beit Shammai says you immerse all before Shabbat. Beit Hillel says kelim, vessels, before Shabbat; and a person [immerses] on Shabbat” (Beitza 17b). Whereas today, we immerse only new vessels in a mikvah, the issue dealt with by the Mishnah is assuring that the vessels are pure—i.e., that were not used by someone who had been to a funeral recently, or who had come in contact with a dead animal—especially over Yom Tov season, when people would be eating sacrificial meat.

The Gemara presents various possibilities as to why one may not immerse a vessel on Shabbat: the fear that one may carry such a vessel in a public area (without the benefit of an eiruv); the fear that one may, where applicable, squeeze out liquid from immersed clothes—clothes being a subset of kelim, vessels; the fear that with the busy schedule during the week, one may specifically wait until Shabbat or Yom Tov to go the mikvah and in the interim handle terumah, rendering it unfit for consumption; or because immersing in a mikvah “looks like fixing a vessel”, a forbidden activity on Shabbat.

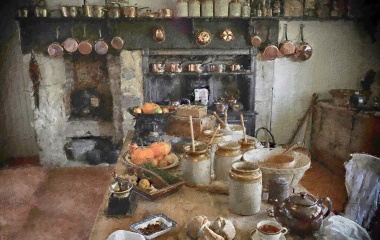

Regarding this last approach, the Gemara immediately suggests, “If so, a person also should be forbidden”, as he is now, in a sense, “fixed” and able to eat sacrificial food. To this, the Gemara replies that “it looks like he is cooling himself”, i.e., that people do not necessarily associate use of the mikvah with religious ritual but as a body of water in which to cool oneself—an ancient swimming pool, if you like. So uncommon were other opportunities for showering that the Gemara explains that such reasoning applies even in dirty water. “Sometimes a person comes home on a hot day and bathes even in water used for soaking linen” (ibid 18b). And the Gemara continues, explaining that such applies even in the rainy season, as “sometimes one comes from the field dirtied from mud and filth and bathes even in the winter”. Hygiene has come a long way since Talmudic times, and even since the 19th century[5].

For us, taking regular showers in clean water is so basic that it has legal import. While traditional halacha rules that mourners are not allowed to bathe, it is generally assumed that today we may do so, bathing being viewed as a necessity and not some extraneous form of enjoyment. This leniency has Talmudic precedent. The Talmud records that Rabban Gamliel bathed the night his wife died. When questioned by his students as to the propriety of such, he responded, “I am not like others—finicky am I” (Brachot 16b).

Rabban Gamliel hailed from a well-to-do family, and—like many blessed with great wealth—was blissfully unaware of the struggles of the less well-off. As his colleague Rabbi Yehoshua told him, “Woe unto the generation that you are the leader, for you do not know the pain of Torah scholars, how they sustain and support themselves” (Brachot 28a). For Rabban Gamliel, and for us today, not bathing for a week or more[6] is oppressive and beyond what is expected of us, even in the midst of mourning.

Yet it was the same Rabban Gamliel who initiated the practice that no matter our material position, all are to be buried alike. “Initially, the burial of the dead was harder on his near-of-kin than his death, so that the dead man's near-of-kin abandoned him [due to the expense] and fled, until Rabban Gamliel came and, disregarding his own dignity, went out (had himself buried) in simple flaxen vestments. Thereafter the people followed his lead and were buried in flaxen vestments. Rav Papa said, ‘Nowadays, all the world follows the practice of [burial] even in a paltry [shroud] that costs but a zuz’” (Moed Katan 28b).

The last honour bestowed upon a person is “bathing” the body in a mikvah to prepare it for burial. There truly is much to learn from the “showering” practices of our ancients.

[1] Elements of realia are included in the Steinsaltz Talmud (Koren) yet are almost totally absent in ArtScroll’s Schottenstein edition.

[2] While the example below is a simple one, and well-known, such is often not the case. For example, understanding the etiquette of how parties were conducted during Roman times will give a fuller understanding of the tragic Bar-Kamtza story (Gittin 56b).

[3] From the Talmudic discussions, one gets the impression that use of the mikvah was common even after the destruction of the Temple.

[4] Interestingly, the Rama (Yoreh Deah 201:75) quotes a custom that women should not take a shower immediately after use of the mikvah, lest people think that the shower is part of the religious ritual of the mikvah.

[5] The notion that hand-washing by doctors would lower the mortality rate was discovered only in the mid 19th century by Ignaz Philipp Semmelweis, and his findings were rejected until proven by Louis Pasteur.

[6] The Shulchan Aruch (Yoreh Deah 381:1) states that the practice of not bathing applied not only during shiva, but for the 30-day mourning period!